“Life is beautiful and life is stupid.” That’s basically the thesis of Catherynne M. Valente’s novel Space Opera, a statement the omniscient narrator makes in the first chapter that becomes a mantra of sorts throughout the rest of the book. It’s a perfect summation of the book itself, although stupid is a little harsh. It actually has a lot on its mind, it’s just that those things are almost completely nonsensical and based more on mood, attitude and capturing a particular feeling of youthful passion that is both completely concerned with a shallow sense of coolness and earnestly sincere in its belief that said coolness can save the world.

With some writers, plot is a priority. They want a meticulously structured framework that builds to a fulfilling climax. Others are all about crafting characters who are fun to hang out with. Still others are more concerned with worldbuilding, as they create a sandbox within which to explore. One might imagine that all three of these are necessary to craft a story, but what about the writer who isn’t overly concerned with plot, character or worldbuilding at all? It’s not that Valente doesn’t include these three aspects in Space Opera, released on April 3, 2018, but they certainly take a backseat to her luxuriating in the written word.

Just check out the description on Amazon.com:

A century ago, the Sentience Wars tore the galaxy apart and nearly ended the entire concept of intelligent space-faring life. In the aftermath, a curious tradition was invented—something to cheer up everyone who was left and bring the shattered worlds together in the spirit of peace, unity, and understanding.

Once every cycle, the great galactic civilizations gather for the Metagalactic Grand Prix—part gladiatorial contest, part beauty pageant, part concert extravaganza, and part continuation of the wars of the past. Species far and wide compete in feats of song, dance and/or whatever facsimile of these can be performed by various creatures who may or may not possess, in the traditional sense, feet, mouths, larynxes, or faces.

And if a new species should wish to be counted among the high and the mighty, if a new planet has produced some savage group of animals, machines, or algae that claim to be, against all odds, sentient? Well, then they will have to compete. And if they fail? Sudden extermination for their entire species.

This year, though, humankind has discovered the enormous universe. And while they expected to discover a grand drama of diplomacy, gunships, wormholes, and stoic councils of aliens, they have instead found glitter, lipstick, and electric guitars. Mankind will not get to fight for its destiny—they must sing.

Decibel Jones and the Absolute Zeroes have been chosen to represent their planet on the greatest stage in the galaxy. And the fate of Earth lies in their ability to rock.

All of that is really just a description of the premise, and it’s essentially established within the first 47 pages of the 294-page book. The 200 pages after that hook are basically Valente pontificating upon broad questions about existence and the meaning of consciousness, all while evoking some of the strangest imagery ever put to page and, most importantly, just being damn funny. Take, for instance, this turn of phrase from page 162: “The time-traveling red panda paused in his epic battle with staying on his own four legs and not spending his entire life arse over teakettle and peered up, deeply annoyed, into the Englishman’s eyes.”

In terms of actual plot, nothing actually happens until the last 40 pages, which I won’t spoil but is kicked off by a threesome between Decibel Jones, a Smaragdin alien and a beam of moonlight. It’s, ironically, fairly anticlimactic and mostly character-focused.

The character focus, however, is essentially on just two characters: the aforementioned Decibel Jones, Dess to his friends (of which he has none during the present day of the novel), and his former bandmate Oort St. Ultraviolet. The former is the lead singer of the Absolute Zeroes and the latter is a “man-of-all-instruments”, and they had a falling out decades ago (setting the novel in some sort of vague near future) over the death of their drummer and keyboardist, Mira Wonderful Star. In the years since Dess has become a bit of a has-been, a drunken buffoon too sexed up and strung out to think straight, while Oort has settled down into domesticity, raising two kids and playing backup guitar for commercial jingles. Most of the drama is drawn out of whether or not their friendship can ever be mended, and most other characters are there as opportunities for Valente to explore their biology and/or philosophies.

The closer comparison to this form of book is, of course, Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. There’s even a comparable text in Space Opera, titled Goguenar Gorecannon’s Unkillable Facts. Described as a “large-print, mildly venomous picture book” that “contains 99.9 percent pure reliable and comprehensive laws of the universe as observed by an underachieving socially anxious murderhippo and is considered to be as essential to a healthy, balanced childhood as hugs, night-lights, and cellular division,” it’s kind of a Poor Richard’s Almanack on crack.

By comparison, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is more of a travelogue of the universe, and of course originates in the novel of the same name. Originally aired as a radio comedy broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 1978, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was, of course, adapted into the novel in 1979, and has had numerous incarnations since including comic books, a TV series and a 2005 feature film (that’s best left forgotten). Needless to say, it and its sequels (four written by Adams, one written by Eoin Colfer) are well known, with several of the books’ catchphrases and ideas taking hold in the cultural consciousness. But it and Space Opera have even more in common, including that they’re almost all hook and very little plot.

Think about what The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is actually about. I tried this experiment with a colleague at work, and we could only come up with a few details and ultimately decided it’s certainly not plot-intensive. Basically Arthur Dent is a hapless Englishman who is saved by his friend Ford Prefect, who also happens to be an alien, before the Earth is destroyed by the Vogons, intergalactic bureaucrats who are creating a interstate through this part of the solar system. Ford, who is a researcher for the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and Arthur eventually find their way to Zaphod Beeblebrox, the Galactic President; Marvin the Paranoid Android; and Trillian, a former crush of Arthur. All together on the Heart of Gold, a spaceship with an Infinite Improbability Drive, they bump around the universe until they discover Earth is a giant computer created by mice who are trying to find the question to the answer of 42.

That’s mostly nonsense and totally at the whim of what Adams is compelled by at any given moment. That means he’s mostly using plot as a framework to allow him to muse in completely random, disconnected ways. What Adams shows within those musings is a remarkable control of tone. He’s funny but in that remarkably British way of being stoic and irreverent at the same time. One cannot mock such a proper way of life without being immersed in it, and Adams’s work is consequently a slice of truth and understanding. It also has a streak of melancholy and yearning to it, but also a lack of sentimentality (something the 2005 movie flubbed).

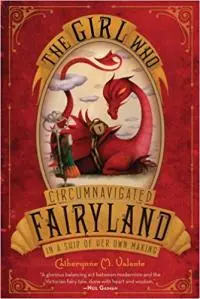

Valente, on the other hand, is very much American but is trying to channel Britishness, although it’s a very different kind of Britishness than Adams. Valente, who has forged a career by deconstructing fantasy and science fiction tropes in books like The Refrigerator Monologues and The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, here attempts to communicate the queer experience and the immigrant experience. Sexuality is something she’s explored quite often in her previous novels, and here it plays into the overall atmosphere. The entire Earth has been queered, the world turned upside down, by the revelation that it's low on the galactic food chain, and also that its inhabitants may not even be sentient and are forced to question exactly what that even means.

Valente, on the other hand, is very much American but is trying to channel Britishness, although it’s a very different kind of Britishness than Adams. Valente, who has forged a career by deconstructing fantasy and science fiction tropes in books like The Refrigerator Monologues and The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, here attempts to communicate the queer experience and the immigrant experience. Sexuality is something she’s explored quite often in her previous novels, and here it plays into the overall atmosphere. The entire Earth has been queered, the world turned upside down, by the revelation that it's low on the galactic food chain, and also that its inhabitants may not even be sentient and are forced to question exactly what that even means.

Comparatively The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is rather chaste, as is most of Adams’s work. Sex just wasn’t something the author was very interested in. The same could be said of Jasper Fforde with his Thursday Next stories, revolving around journeys inside of books and a comparative reveling in the beauty of wacky concepts and language. Valente’s willingness to reframe taboo behavior into something that’s completely casual and even expected is much more along the lines of Neil Gaiman. But even with Gaiman he’s very concerned with who are and aren’t the outsiders, and there can’t be outsiders without insiders. No, Valente paints a universe where only the weird can save the world, and there’s not much in the way of debate about morality or rightness.

The intersection of sexuality and the question of what constitutes Britishness is summed up in the lead character of Dess. Birth name Danesh Jalo, he is of Pakistani, Nigerian, Welsh and Swedish descent but according to Valente he is very much a Brit. As the author puts it, “For his part, little Danesh inhaled a heady, unleavened diet of science fiction films, despite his grandmother’s insistence that they were neither halal nor anywhere near as good as Mr. Looney of the Tunes, as she called her favorite American programs.” That sets up a running gag of sorts, as Dess sees the aliens who tell the Earth about the Grand Prix, the Esca, as Road Runners like in the cartoon. It also establishes the tension of Nani, with her old world sensibilities, and Dess, with his universal love of pop culture that isn’t defined by nationality.

And sexuality wise he’s unapologetically fluid, and the novel itself supports this. As Goguenar Gorecannon’s Fourteenth Unkillable Fact states: “Everyone fucks.” This is presented rather casually, as with the introduction of Dess’s bandmates, the aforementioned Oort St. Ultraviolet and Mira, who tragically dates Dess. They meet at a club and, of course, a threesome results, although this is only a one-time thing as “Oort was mostly straight and hardworking, Mira was mostly monogamous and militantly cynical, and Decibel was mostly none of these things, except when he thought they’d look good with a paisley coat.” Point being, anything goes as long as all parties consent, because as the Fourteenth Unkillable Fact concludes, “There is no atom in this galaxy but that someone hasn’t tried to fuck it.”

All of this isn’t a read for everyone. It’s light on forward momentum and ultimately is brought full circle by a deus ex machina. But it’s a “hangout novel,” is what it is, a world and set of broad personalities that Valente crafts so she can indulge in imagination. Furthermore, it offers up a familiar kind of whimsy pioneered by previous authors tapped into this vein of Britishness, even if this time it’s written by an American, but with the added flavor of new kinds of skin colors and new sexual proclivities described in vibrant and living detail. Consequently, it’s a delight just to read this poetry disguised as prose.

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.