All the poetry images in this article used by permission of the poet, Jessica McHugh.

Blackout poetry has been called a number of different things across time. It’s been called redacted poetry/writing, found poetry, erasure poetry, and it crosses over into cutout poetry and collage art. Even when you call it blackout poetry, as most people do these days, there’s not a clear consensus online whether it is “black out” or “blackout.” It’s probably safest just to use the hashtag #BlackOutPoetry, then it doesn’t matter whether it is compound word or not. Hashtags save us again.

What is it?

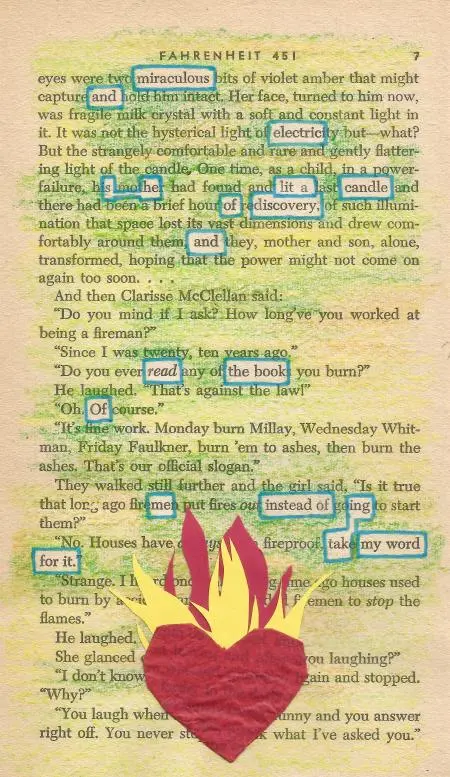

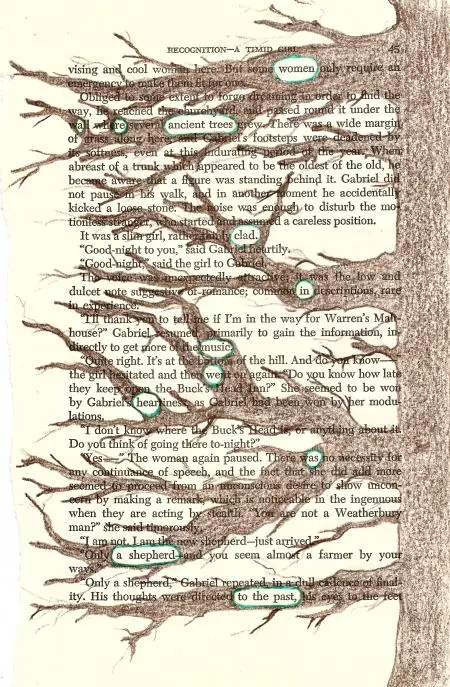

Blackout poetry is preserving some words while redacting the rest on a preexisting or “found” piece. That piece can be a newspaper article, a document, or a page from a book. This is used to create a poem or other piece from the isolated words. It produces something new, different, and creative out of and apart from the original source material.

In the past, the rest of the page with all the unused words were literally blacked out, leaving only the pattern of selected words. As time has gone on, the blacking out process has turned to drawing other artwork over the page, different ways of boxing off or circling the selected words, different patterns of words around the page, and even collage and craft elements being added to the pieces.

Old and New

The origins of playing with text in this manner go back pretty far, depending on how loosely you define the art form. Word codes used as early as the 1700s are sometimes credited as being part of the origin of blackout poetry. Various shape poems through the centuries can be seen as contributing to the aesthetic. Dadaism in the early twentieth century is well known for pushing back against traditional forms, and cutout poetry was a part of that. Moving forward, that familiar look of words formed from cutting out different letters in different fonts to create messages or poetry was one that many people recognize. By the 1960s, true blackout poetry was practiced by a number of accomplished poets and artists. Already, it had all the experimental elements that many poets utilize within the art form today.

Blackout poetry occupies an unusual space that crosses over heavily between written composition, visual art, and crafting. Like any craft, it has a niche of people fiercely loyal to it. If you go on Instagram right now and type in the hashtag #BlackOutPoetry or #BlackOutPoetryCommunity, you will find some of the most incredible art and poetry you’ve ever seen. You can find examples the same way on other social media platforms too.

There is a resurgence of interest in this artform. A number of key writers and poets are sharing more of this type of work across social media. More people are using it in art therapy. More teachers are including it as part of poetry curriculum in school.

A Case Study

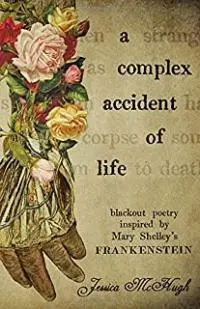

The best way I can think of to explore the form and its process is to focus on one poet and her work in detail. This article really exists because of Jessica McHugh. I sat down for a conversation with her as I prepared to write this piece. We recorded that discussion. All the poetry images in this article are used by permission of the poet, Jessica McHugh.

Jessica McHugh was recently nominated for a Bram Stoker Award for her blackout poetry collection a complex accident of life that included poems derived from a particular volume of Frankenstein. She has been doing commissions of blackout poetry for a while now, and has been offering blackout poetry on her Patreon page monthly for supporters at a particular level.

She has experienced hardship and loss in her life that informs all areas of her writing. It was with the recent death of her brother that she turned to her ongoing work with blackout poetry to process the grief. As she posted more and more of her deeply personal blackout poems, she started to apologize for filling up everyone’s feeds on social media. The overwhelming response was that people wanted to see more. The requests for commissions increased to the point that she had to establish a website portal to manage all the work. She does not recommend running as many as seven commissions at once, but McHugh has done so successfully.

As a successful novelist and short story writer, poetry has never really left the background of her writing journey. She credits her professional interest in blackout poetry with a convention/writing conference she attended where a blackout poem was included in the goodie bag for participants.

As a successful novelist and short story writer, poetry has never really left the background of her writing journey. She credits her professional interest in blackout poetry with a convention/writing conference she attended where a blackout poem was included in the goodie bag for participants.

As she has gone on to create more and more work in this style, there is a certain anxiety that goes along with it. These are original pieces being created in a physical one-of-a-kind form. A mistake with ink or a smudge over an important word can ruin the piece. Without multiple copies of the exact same version of the work, you don’t get a second chance. Still, she has made strides with bolder and braver choices with the art and collage she has included within the works. And therein lies another quirk of this artform. Original pieces are sent to those who commission them or buy them. She can photograph and scan the pieces, but none of those create perfect copies of the originals. McHugh says she feels like the scans are counterfeit ghosts of the unique pieces, but she takes comfort in knowing the singular work is treasured by the person who bought the original art and poem.

Walking through her process, it begins with either she or the patron the commission selecting a book. Jess asks the patron what themes or color schemes they’d like her to use. On any given page, she seeks out an anchor word— some word that is going to lead her into a metaphor or simile for the poem. Then, she has to scan down or spiral out from there to see if there are enough supporting words to carry the idea forward and to end the poem well. She has often gone left right and top down in a very Western style of reading, but words can travel out from the beginning in most any direction. As a personal choice, she tries not to construct words by pulling letters from multiple words, but the writing styles found in some of the source materials may require it. After picking the words that make the poem, she decides how she is going to isolate them and then what colors, drawing, and art styles are going to complete the piece.

Having been nominated for an award for this work, there is almost an obligation for her to create more of it. I asked about copyright concerns. She said there were advantages in sticking with works in the public domain if you intended to publish a book of blackout poetry. Readers knew the work better and it avoided copyright entanglements. Blackout poetry does have a unique distinction in that it is transformative art. Since it does not tell the same story, it is considered something different from the source material, perhaps in a similar way that commentary on a piece is usually protected. Or maybe how Andy Warhol got away with painting Campbell’s Soup cans. Whether Campbell’s Soup could have won a lawsuit against Warhol in the 1960s is not one hundred percent clear due to the fact that they opted not to, being satisfied with the invaluable brand awareness his work brought them. Other authors might not have Campbell’s-Soup-levels of grace.

Her dream project would be to get permission from Peter S. Beagle to create and publish a collection of blackout poetry from The Last Unicorn. She has met him and got along well with Beagle, but with his current legal struggles over his literary legacy, she’s not sure he would be open to the idea.

Blackout poetry, much like most types of art and writing, is potentially open to anyone to try. It’s hands-on work. It engages multiple facets of creativity. There is a unique product at the end of it. Like all forms of writing and art, there are big gaps between those who are great at it and everyone else. That does not take the joy out of the creation process, though. If anything, it adds to the wonder and beauty of what great poets and artists create for us to enjoy. McHugh said that she spent twenty-five years thinking she couldn’t draw until blackout poetry showed her otherwise. It is worth checking out because there must be some reason this artform is gaining attention again.

Get a complex accident of life at Amazon

About the author

Jay Wilburn lives with his wife and two sons in beautiful Conway, South Carolina. He is a full-time writer of horror and speculative fiction. Jay left his job as a teacher to become a full time writer and has never looked back. Well, that’s not entirely true. He wants to be sure he isn’t being followed, so he looks back sometimes.