We’ve all been there. Some well-meaning mentor, professor, or internet guru drops a golden nugget of writing wisdom, and you cling to it like a life raft. But here’s the thing: a lot of so-called "good advice" is actually garbage; either outdated, misunderstood, or just plain counterproductive.

So let’s dismantle some of the worst offenders, shall we?

1. "Write every day!"

On the surface, this sounds solid. Discipline! Routine! Consistency! But here’s what they don’t tell you: forcing yourself to write daily, regardless of energy or inspiration, can fast-track you to burnout and writer’s block. It turns writing into a chore, and before you know it, you’re dreading the thing you supposedly love.

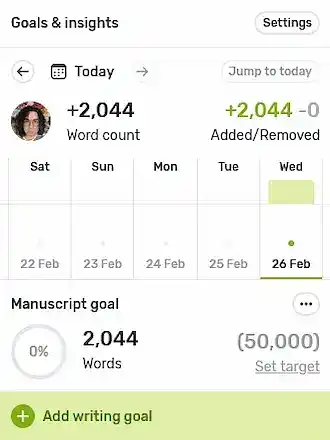

A better approach: Build a sustainable habit. Writing three to four days a week, or even setting flexible word count goals, allows for consistency without destroying your motivation (Reedsy Studio is great for this). Forming a habit is important, but if you sit down to write and it’s not happening, you don’t have to force yourself. As the adage goes, quality > quantity.

2. "Break the rules!"

Rules are meant to be broken — if you know why they exist in the first place. The problem is that new writers sometimes take this as permission to ignore grammar, structure, and a coherent and well-developed story.

Some iconic writers like James Joyce, Cormac McCarthy, and Toni Morrison bent the rules to serve their stories. They didn’t just ignore them because they didn’t feel like using punctuation that day.

McCarthy, to be specific, uses almost no traditional punctuation in his sentences; resulting in either long and flowing segments that require concentration to parse, or short, dry, and somewhat stoic utterances that help give a unique feel to his settings and characters.

In a similar vein, James Joyce often chooses to forgo punctuation entirely, but he does so with the purpose of mimicking the nonlinear, chaotic and nebulous nature of his stream-of-consciousness writing of internal dialogue.

A better approach: Learn the rules first and understand why they’re important. Then, if you’re going to break them, do it with intention and consistency.

3. "Work on a chapter until it’s perfect!"

This isn’t really common advice, but rather a common trap that many authors fall into because we are all at heart perfectionists when it comes to our writing. But this is exactly how you fall into the perfectionist’s death spiral: trying to polish every sentence before moving on to the next one is the best way to ensure you never finish a draft (or, indeed, ever reach sentence #10).

Your first draft is supposed to be a mess! That’s why editing exists in the first place. Especially if this is your first project as an author, you’ll find the first draft of your first chapter will likely require much more editing work than the rest of the book — but you can’t get to the rest unless you have a foundation from which to write further.

A better approach: Get the words down. Let them be ugly, and learn to embrace the ugliness. Your first draft should be the place where you focus on working through your main ideas instead of perfecting them right away. And when in doubt, remember Jane Smiley’s (good) writing advice: “Every first draft is perfect because all the first draft has to do is exist. It’s perfect in its existence. The only way it could be imperfect would be to not exist.”

4. "Revise, but don’t rewrite!"

We’ve talked about getting addicted to editing and polishing, but here’s the other side of the coin: there are authors who get stuck working on a single chapter, and there are authors that churn out page after page without ever looking back.

Writing is rewriting. Your first draft is you telling yourself the story. The second (or third, or tenth) is where you make it good. If you had a lot of trouble getting the first draft just right, it’s only natural that you will feel hesitant to scrap even small segments of it later on, but it’s a necessary step of the writing process.

A better approach: Accept that revision is part of the process. Consistent rewrites can improve and clarify writing as your skills improve, especially in long-term writing processes like novels.

By the time you write the last chapter, your skills as an author will be on another level compared to when you started the first page. Your familiarity with your own story and what you want it to be will be more fleshed out, too. Don’t be afraid to give your book a second pass and rewrite liberally.

5. "Write only what you know!"

There’s a reason this advice is common nowadays, when deeply personal accounts of traumatic circumstances or intensely emotional relationships are popular subject matters. If you write about what you haven’t experienced in the flesh, you run the risk of portraying some themes inaccurately or insensitively.

And yet, if authors actually followed this advice, we wouldn’t have genres like sci-fi, fantasy, or historical fiction. Tolkien never visited Middle-earth — and I’m pretty sure Mary Shelley never reanimated a corpse!

This doesn’t extend only to speculative fiction, literary and historical fiction can benefit greatly from writing outside of personal experience. Annie Proulx, for instance, was not a repressed cowboy when she wrote Brokeback Mountain. Nor was Agatha Christie a professional murderer (as far as we know).

A better approach: If you have a book idea that speaks deeply to you — but isn’t in your realm of knowledge — we have one word for you: research! Access to information is easier now than ever in history. Take great advantage of first-hand accounts of experiences you’ve never had, watch documentaries or read nonfiction books about freak circumstances or events you want to incorporate into your story but never experienced yourself.

Above all, remain mindful and empathetic if you’re incorporating a theme that’s potentially delicate or controversial to handle. Be extra thoughtful in your research in these instances, and consider getting help from a sensitivity reader. Consulting with people directly affected by such topics is always recommended.

A great example of this is Mark Haddon, who wrote The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and did a lot of research on autism in the process of doing so.

6. "Take advantage of [current trend]!"

Forcing your novel into the bestseller list through the abuse of a hot trend might sound like a shortcut to success. But trends are fickle, and by the time you’ve finished your “dark academia cozy vampire romantasy in first-person,” the market will have moved on.

Take the Twilight saga: the vampire craze that rode its coattails was intense, but short, lasting only a few years. The traditional publishing cycle is also typically one or two years long. By the time you get your fad-ready book out there, the bandwagon you sought to jump into may indeed have departed long ago.

A better approach: Be authentic. Trends are well and good, and they’re popular for a reason — if you want to add an element that’s in vogue to make your book pop out from the bookstore shelves more easily, there’s nothing wrong with that.

However, unique and well-crafted stories stand out more (and longer) than trend-chasing cash grabs competing in a saturated market. Who knows? You could be the one to start the trend.

7. "Ask for feedback from everyone!"

Seeking feedback is great, but too much feedback is paralyzing. If you’re showing every chapter to ten different beta readers, you may very well get ten conflicting opinions on a single chapter. By then, it’s easy to not know which one to trust, and lose sight of your vision.

This applies not only to the amount, but also to the frequency of the feedback you receive. Sending every chapter to your friend to ask their opinion will get you in a nitpicky mindset, in turn making your process slow to a crawl and “miss the forest for the trees.” (Remember our previous warning about not working on a chapter until it’s perfect?)

A better approach: Get feedback at the right time—preferably after you’ve got a solid draft of the whole story. And choose your readers wisely: if not an author themselves, at least an avid reader with a strong frame of reference and literary knowledge. Be judicious when choosing beta readers and seek help only from people that you trust to have opinions, tastes, and references relevant to your book and your process specifically.

8. "Avoid reading within your genre"

This advice isn’t that common (luckily, because it’s terrible) but I’ve seen it in online writing communities. Some people claim that reading other books in your genre will make your writing derivative.

To this, I’d say: you think great musicians don’t listen to music?

Genres and subgenres have conventions: a common framework or language that dictates what works and what doesn’t. Gaining an intimate understanding of what’s been already done within your space and why it was successful will allow you to tread a new path while implementing tried-and-true elements from other stories.

A better approach: Read widely — both inside and outside your genre! Know what’s out there. Learn from it. Most importantly, figure out what works and what doesn’t, and more importantly why. If you don’t read at all, you’ll think your story about a boy wizard going to magic boarding school is brilliantly original.

9. "Don’t outline!"

"Discovery writing" (a.k.a. making it up as you go, or “pantsing”) works for some people, but going in blind can also lead to plot holes, meandering stories, and abandoned manuscripts.

I get it: for a lot of people, outlines feel restrictive and could make your writing end up reading rigid. But in the grand scheme of things, they’re more useful than restricting, especially in genres where you need to keep meticulous track of every character and their actions, such as mystery and thrillers. While some people like to plan ahead and some others work better on the fly, it’s useful to at least have the core components, characters, and events of your story in writing. It doesn’t have to be extensive, it can even be a post-it with a few keywords. What’s important is that you know what you’re aiming for when writing.

A better approach: Outlines aren’t the enemy. Even a loose roadmap can keep your story on track. You don’t need to stick to your outline like it’s the ten commandments. Think of it instead as a general set of guidelines that you yourself impose and choose when to stray away from.

10. "Memorize all the theory"

Yes, knowing story structure and character archetypes is useful. No, treating them like a rigid checklist isn’t. Trying to tick every box will leave your writing feeling mechanical and soulless.

Plus, savvy readers are also familiar with common character archetypes and their corresponding development arcs, as well as concepts like “The Hero’s Journey.” If you rely on these too much, your story will become predictable and formulaic. Trust me: readers don’t want to play a game of Bingo as they’re reading your book, methodically crossing out “Appearance of the old wizened mentor figure” or “It’s time for the third-act breakup” each time they cross across them!

A better approach: Learn theory, but let your story breathe. Write with instinct, not obligation. Just as with grammatical rules, familiarize yourself with storytelling concepts so you learn how and when to break them and make them work for you. Once more: reading within your genre is valuable because it helps you understand how other people have subverted or subscribed to these conventions before, and which is the better approach for your own story.

Writing advice isn’t one-size-fits-all. Just as someone’s story is messy and inconsistent because of a lack of an outline (for example), there’s another author out there struggling with a stiff and robotic story because they stick to their outline too much.

The key is knowing when to apply each piece of advice and when to ignore it. Find what works for you, but stay open to growth. Be critical, trust your instincts, experiment, and most importantly, keep writing. (Just... maybe not every day, as we discussed!)

About the author

With a background in journalism and content-focused digital marketing, Adrian now harnesses a lifelong passion for reading and writing to post on the Litreactor and Reedsy blogs about creative writing tips, the publishing process, and the current trends in diverse literary spheres. He's constantly torn between numbers and letters; if there's data, charts, figures, and percentages, you can be sure Adrian will break it down into a digestible, simple, and (sometimes) brisk read.

Outside of work, Adrian enjoys experiencing narratives through the unconventional medium of videogames, fussing over his aquarium's water quality parameters, and holding regular check-ins with a variety of tarot decks.