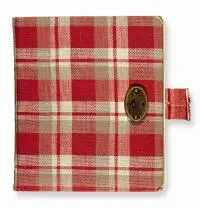

On June 12, 1942, a little girl named Annelise Frank received a diary for her birthday. It was on the small side, covered in a red and white checkered fabric, and it would go on to contain some of the most famous diary entries ever written.

Half a century later, a little girl named Leah purchased the published version of Anne's diary while on a trip to Washington DC to see the recently-dedicated Holocaust Museum. She thumbed through that small, black paperback on the four hour train ride home, devouring Anne's words. Imbibing them like a fine wine, letting them simmer and fester. Letting them roll around in the back of her head for months on end.

The diary inspired fourteen-year-old Leah. Leah and Anne's birthdays were fifty years and five days apart, but their lives felt similar anyway. Both girls were Jewish, yes, but that wasn't the important thing.

Both girls were terribly lonely. Anne Frank wrote:

I have about thirty people whom one might call friends - I have strings of boy friends, anxious to catch a glimpse of me and who, failing at that, peep at me through mirrors in class. I have relations, aunts and uncles, who are darlings too, a good home, no - I don't seem to lack anything. But it's the same with all my friends, just fun and joking, nothing more. I can never bring myself to talk of anything outside the common round. We don't seem to be able to get any closer, that is the root of the trouble. Perhaps I lack confidence, but anyway, there it is, a stubborn fact and I don't seem to be able to do anything about it.

Hence, this diary.

That was the statement that made fourteen-year-old Leah realize: she was not alone.

So Leah began to write.

Yes. She would write.

Yes. She would write.

She bought a notebook, labeling it "journal", as "diary" sounded a bit too feminine. In the journal, Leah wrote. Oh, she wrote and she wrote, about troubles at school, about fights with friends. She wrote and she whined about her siblings, her parents. She rumbled and grumbled and wrote some of the most pedestrian journal entries ever to fill a notebook.

When she sat down to read what she'd written, hoping to find writing as good as Anne Frank's, of course she found trash. Drivel. Terrible sentences full of cliches and detritus.

Her heart broke, and she almost never picked up a pen again.

Anne Frank had been hiding in the secret annex for over a year, writing in her diary often, when she heard a special radio announcement, broadcast from outside the Netherlands. Government agencies, it said, wanted diaries and journals kept during the war years. They could be used as important historical records, telling the rest of the world what those in occupied countries endured at the hands of the Nazis.

Anne heard this and was inspired. Her diary, an important historical record? Perhaps...eeep...published?

She began to read through all she'd written and found, like so many young diarists do, that it wasn't exactly worthy. Anne was stubborn, though. She wouldn't give up. No. She could make her diary something to be proud of.

Anne could edit.

From that day on, Anne not only wrote new journal entries, recapping her final years in the annex, but she edited her old entries as well. She spent hours each day going through what she'd already written. She added entire pages from memory, recapping important incidents with care that she hadn't used before. She crossed out sections she didn't like, removing bits that were too personal or too mundane.

By the time of her family's capture in August of 1944, Anne's original red-and-white-checked diary was stuffed full of extra papers, each carefully dated. When the police raided the annex, they saw only a child's journal. They scattered the papers across the floor, having no idea how many incriminating details they'd left behind. Miep Gies, one of the family's main caretakers during their time in hiding, found the papers, collected them, and kept them in a drawer, awaiting Anne's return.

Of course, Anne never returned.

When her father, Otto, arrived in Amsterdam after years of grim existence in Auschwitz, there was still hope his girls (Anne and her sister, Margot) were alive. The diary remained locked in the drawer, each and every paper Miep had collected, awaiting Anne's return. It was only after Otto received word that his daughters died, days apart, at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, that Miep opened the drawer. Now that Anne was gone, the diary was Otto's.

He sat in the office of the building in which he'd hidden with his family and read Anne's carefully edited diary. He read the good bits. The sad bits. The joyful bits. He also read the bits about how angry Anne often was with her mother, Edith. How hurt she often was. How alone she often felt. He read the bits about Anne falling in love with Peter, her partner-in-captivity. He read her doubts, her fears.

By then, there was no doubt as to Anne's intent for her diary. She'd been so carefully editing it for so long. She wanted it published, so that's what Otto pursued, but not before carefully curating her journal, removing unflattering images of his wife, his daughters. Himself. Anne's original diary as compared to the published one is a very different entity indeed.

Several years ago, at my favorite local bookstore, I came across a beautiful copy of The Diary of Anne Frank - The Critical Edition - Prepared by the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation.

Oh God, if only Anne knew her diary had been published, carefully annotated and prepared, by a State Institute for War Documentation. If only she knew how important she became. It would have been her dream come true.

But I digress. That's not the point of this article.

But I digress. That's not the point of this article.

Inside this massive tome, one finds handwriting analysis documentation to prove to all the doubters that Anne Frank, indeed, wrote her own diary. One finds a detailed history of Anne's family, going back several generations. One finds the sad accounts of life for the family and their keepers after the raid at the Secret Annex. One finds, too, the handwritten letter that told Otto his daughters were dead.

But what I find most interesting about the critical edition is this: in its pages, one finds three versions of Anne's diary entries - the bits she originally wrote, the bits she cut out as not interesting enough for publication, and the bits she carefully added and edited, jazzing things up, making sure her writing was up to par.

Those first bits are the bits I wish I could show to fourteen-year-old Leah.

I wish I could show her the pages upon pages of writing cut from Anne's published diaries, outlining the various conversations with school friends, the clubs formed, the clubs abandoned. She wrote so much about her friends early on, just as fourteen-year-old Leah found herself doing.

Anne cut those entries from the diary she intended to publish; I'd have cut them as well.

Anne wrote entire pages in stream-of-consciousnses rambles, foregoing paragraphs and punctuation as she rushed to put her thoughts to paper. It was only on editing that Anne added formatting, corrected spelling, and made sure her sentences even made sense.

Anne was the one who added full pages for clarity, taking the time to recreate events from memory so her future readers wouldn't be left scratching their heads, wondering what in God's name this little girl was talking about.

Anne Frank, the writer of the world's most famous diary, also happened to be one of the sharpest editors I've ever seen.

Were she still alive, this week Anne would turn 87.

I wonder if she'd still read her own diary.

Or I wonder if, like most of us, her own words of the past, words that seemed so important at the time she wrote them, would make her cringe. Would make her want to hide.

What I do know is this: Anne died long before she ever became famous, but her work — her carefully edited and curated work — lives on, touching lives, changing perspectives. I'll tell you this, too: I can't wait to see what happens when my own little girl reads Anne's published diary for the first time. I can't wait to see if it inspires her.

And if it does, I'll be sure to let her know what a great editor Anne was. No need in paralyzing my little girl when she realizes her rough, wild, stream-of-consciousness drafts will never live up to Anne's carefully reconstructed diary.

About the author

Leah Rhyne is a Jersey girl who's lived in the South so long she's lost her accent...but never her attitude. After spending most of her childhood watching movies like Star Wars, Aliens, and A Nightmare On Elm Street, and reading books like Stephen King's The Shining or It, Leah now writes horror and science-fiction. She lives with her husband, daughter, and a small menagerie of pets.