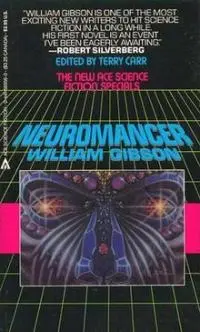

Cyberpunk has traditionally been dominated by male characters and the male perspective. After all, the works of proto-cyberpunk—Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination (1957) and the movie Blade Runner (1982), based on the book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sleep? by Philip K. Dick—were all written by men and feature male protagonists. These were influences for William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), the book that defined a genre, and whose “console cowboy” main character is a man named Case. And yet even with the influential precursors there was always a female presence, and Neuromancer plays into this with a memorable supporting character Molly, the first of the “razorgirls.”

Jump ahead a little over 30 years later, and Annalee Newitz’s Autonomous is the answer to a male-dominated genre. Not only is it written by a woman, it stars two female leads, Jack and a robot named Paladin that is complex in her gender, who both blur the lines of sexuality and identity. Once the Editor-In-Chief of Gawker-owned media venture io9 and Gizmodo after that, she is as of 2016 the Tech Culture Editor at the technology site Ars Technica and prior to Autonomous had written five non-fiction books covering technology. So her book sees the combination of her identity as a woman and predilection towards futurism. Contrast that against Neuromancer, its influence on cyberpunk and the legacy that followed it.

Cyberpunk in of itself is a very male-centered genre. It has a cynicism and nihilism that takes its lead from noir, the form of fiction that sprung out of the Great Depression. Noir tends to focus on male leads, private detectives or criminals that find themselves pulled into a greater world, usually contrary to their intentions. In the face of this world they’re overwhelmed with the daunting abyss. Authors such as Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler dealt with this, and years later Gibson would apply that mood. Prior to Neuromancer science fiction tended to be more inspirational, with a view toward a future in which man overcomes his worst impulse. With cyberpunk, however, it’s a decaying world of anxieties over corporations and xenophobia over invading businesses, especially by Japan, and especially of the negative consequences of technology. At the center of this is Case, a low-level hustler that has had his nervous system destroyed with a mycotoxin. Case is offered a cure, however, in exchange for doing a job, and the first thing Molly does after he is cured is initiate sex with him.

Now Molly is a fascinating character. Introduced in the short story “Johnny Mnemonic” from Gibson’s collection Burning Chrome (1986), she makes several appearances across his many books and goes by a few different names. In Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988) she goes by Sally Shears, and in Neuromancer she’s just Molly without a surname. She’s an enhanced bodyguard/mercenary cyborg known as a “razorgirl” because she has razor-sharp retractable blades underneath her fingernails. She wears mirror-shade sunglasses, creating an aviator-like cool, but can’t take them off as they are actually sealed to her face. This all certainly contributes to her being a strong and intimidating figure, but it keeps her at a distance and more idealized than anything.

The works that would take influence from Gibson were similarly hesitant to position a female as the main character. Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, released in 1992, could arguably be said to be a two-hander between Hiro Protagonist and Y.T. (Yours Truly), but again, only the male character gets any introspection or flaws while the female is a mysterious badass. In Y.T.’s case she’s a skateboard-riding courier that’s too cool for school. Similarly The Matrix, arguably the only movie to really pull off the cyberpunk aesthetic and attitude, shies away from Trinity’s perspective after it opens focused on her. She steps aside to let Thomas Anderson, aka Neo, step into the role as audience surrogate. In retrospect this is, of course, fascinating because the Wachowskis were men at the time but later transitioned into women, so it’s hard to say what perspective they brought to making the movie and releasing it in 1999.

Cyberpunk burned fast and bright, with Snow Crash being labeled in some circles as post-cyberpunk due to its satirical bent, and The Matrix adapting the whole genre after the fact. These days the genre has all but gone away, with a few late bloomers attempting to adapt to a world that more and more is looking like the future that was predicted. Richard Morgan’s Altered Carbon, released in 2002 and just this year adapted to a Netflix television series, has an urban sprawl setting not unlike its predecessors and attempts to tackle the question of the soul, with people downloading their consciousness into cloned bodies to avoid death. It’s one of the few modern attempts to play the material straight, and even leans hard into the noir angle with the main character investigating a murder, while Cory Doctorow’s Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, released in 2003, mostly pokes holes in the ridiculous way people interact with technology and engage with nostalgia. Not coincidentally it also has people achieving immortality through hard copies of the human mind.

But again, those were all written by men. The same can be said of male creators in relation to ancillary cyberpunk works like manga and anime such as Akira (1988) and Ghost in the Shell (1995), and even creators that adopt the tropes of cyberpunk on occasion, such as Christopher Nolan with Inception (2010) and Ernest Cline with Ready Player One (2011). A quick perusal of Wikipedia only comes up with a few female cyberpunk authors, namely Pat Cadigan (Mindplayers, Synners) and Melissa Scott (Trouble and Her Friends). Looking at the few collections of cyberpunk short stories, Mirror Shades: The Cyberpunk Anthology (1986) and Hackers (1996), only Cadigan’s name makes an appearance. Needless to say, it’s a male-dominated genre, and that certainly could be said of a lot of science fiction.

Fast-forward to 2017, and the world has caught up to cyberpunk. The Internet and social media dominate our lives, drones fly over our heads, and our eyes and attention are constantly glued to hand-held computers that are so much more than just “phones.” As much as Blade Runner prioritized a revolution in energy rather than communication, with flying cars and space travel but little in the way of portable devices, the cyberpunk that followed it could only predict so much. William Gibson, after all, coined the phrase “world wide web,” but he and Stephenson’s conceptions of the Internet seem antiquated in retrospect.

Fast-forward to 2017, and the world has caught up to cyberpunk. The Internet and social media dominate our lives, drones fly over our heads, and our eyes and attention are constantly glued to hand-held computers that are so much more than just “phones.” As much as Blade Runner prioritized a revolution in energy rather than communication, with flying cars and space travel but little in the way of portable devices, the cyberpunk that followed it could only predict so much. William Gibson, after all, coined the phrase “world wide web,” but he and Stephenson’s conceptions of the Internet seem antiquated in retrospect.

These days Black Mirror is the science fiction work that is tapped into the vein of disruptive technology, and that’s the landscape Annalee Newitz’s Autonomous appears in, but with a unique focus: the pharmaceutical industry. Set in the 22nd century, the novel focuses on Jack Chen, a pirate raging against patent law. Within her private submarine she develops and distributes free drugs and passes them on to the poor. There’s an obligatory evil corporation, however, called Zacuity, that has released a drug for productivity that turns out to be addictive and leads to people’s deaths. Jack has reverse-engineered this patented pharma, having missed the ill effects, and accidentally created an epidemic. While she enlists allies in order to find a cure and out the machinations of Zacuity, she’s pursued by two International Property Coalition agents, a man named Eliasz and a robot named Paladin, with the latter more interested in the former than their mission.

Newitz brings expertise from her io9 days to her prose. There’s an incredible authority to how she tackles the health care industry and late-stage capitalism, building on the bleak criticisms of previous cyberpunk works while injecting an exigent sense of legitimacy. This understanding of the effects of our current world on the future feels authentic in a way that is horrifying and inevitable. Of course, that’s probably what people felt when reading Neuromancer in 1984.

What’s even more important is the rare-for-sci-fi perspective Newitz brings to Jack and Paladin. Jack is fierce and intelligent, and unapologetically sexual. She falls into a physical relationship with Threezed, an indentured servant of sorts, early on that is mutually beneficial, and flashes back to relationships not just with men but with women from her past.

Then there’s the compelling complexity of Paladin. A military-grade robot, for the first half of the novel Paladin allows herself to be called “he” by Eliasz. Paladin does have a human brain, but at first is unaware of her origins. After a brief but intense physical experience with Eliasz, she senses that he is sexually attracted to her, but he resists any discussion of the matter, claiming he’s not a “faggot,” showing that there is still this kind of prejudice in the future. Further research reveals to Paladin that her brain came from a woman, and telling Eliasz this suddenly makes him comfortable enough to admit his sexual attraction to the robot. Paladin, however, only accepts the pronoun of “she” to make Eliasz happy, and grapples with this question of self throughout the rest of the book.

A male author writing in the wake of cyberpunk could craft a science fiction book that shines such a light on Big Pharma and the destructive effects of capitalism. What Newitz brings, however, is not just her technical knowhow, but a fresh take on female characters and the implications of technology on gender. Hopefully Autonomous sets the kind of precedent for representation in science fiction that William Gibson did with Neuromancer when he created a whole new genre.

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.