Header and photos by Annie Connole

I had been itching to visit the Eaton Collection since last year, when our local Space Cowboy Books did a live online interview with its curators; exploring the aisles, behind the scenes inner-workings, and history of one our country’s largest archival collections of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. When my pitches opened up, I made sure it would be my next piece for Lit Reactor — a two birds with one stone reason to finally bask in its hallowed walls. Accompanying me would be Annie Connole (author/photographer of mythic memoir The Spring), an extra pair of fresh eyes who would also be taking photos.

Located on the fourth floor of the Tomas Rivera Library at University of Riverside, the collection was the property of Berkeley physician Dr. Eaton, who passed away 1968. A year later, his wife would arrange for it to come to UCR. It would be one of, if not the first, intact sci-fi libraries hosted by an institution, heralding a new era of sci-fi education; a look back on its history, its present, and the paths it may pave for the future. Though he was not a writer himself, Dr. Eaton was a vital part of the Bay Area sci-fi fan community, rubbing shoulders with Asimov, Bradbury, and other luminaries.

The library’s first curator was writer/science fiction critic George Edgar Slusser, who came to UCR in 1979, to the English department as a comp lit professor. Slusser discovered Eaton’s collection in the basement, shamefully forgotten, collecting dust. Since no one had done anything with it for nearly a decade, he took on the Eaton collection as his personal project, a labor of love. While Eaton’s donation was 7500 books, Slusser turned it into several hundred thousand, the inventory exploding exponentially over the next twenty years. The Eaton would inspire several institutions acquiring similar collections; universities in Texas, Iowa, Kansas and even Liverpool in the U.K. would go on share the Eaton’s enthusiasm for science fiction literature/ephemera in their educational settings.

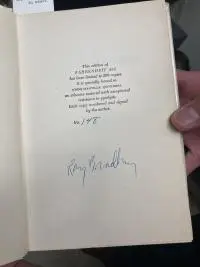

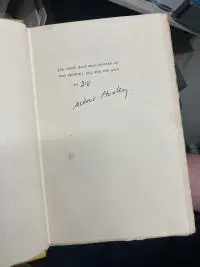

Upon arrival, we met curator Andrew Lippert in his office, allowing him to lead us into the Eaton’s labyrinthian halls. Our first stop: “The Vault,” containing some of the library’s more precious items; the first issues of Black Panther, a whole shelf of 1st edition Lovecraft from Arkham House, a signed and numbered first edition of Brave New World, a signed Fahrenheit 451 (limited to 200, it comes ironically bound in a special asbestos material for exceptional resistance to fire), an original printing of H.G. Wells The Time Machine (complete with glaring typo insisting he was, in fact, H.S. Wells), then, a copy of Thomas Moore’s Utopia from 1517, which Andrew was quick to point out as “literally irreplaceable,” showing its binding made from a re-used animal skin, either cow or sheep. He allowed us to feel the strong craftsmanship of the paper inside, more built to last compared to what we see in books today. “These were really treated like pieces of fine art, how they should be intended,” said Andrew, lamenting an element of publishing devolution.

As we exited the Vault, a bust of L. Ron Hubbard prompted me to inquire about Jack Parsons items, since those two geniuses were toxically, if not karmically intertwined. But Andrew noted the collection has little to no interest in the occult – an indication of the Eaton’s rigid guidelines of curation.

Carrying on, Andrew guided us to the expansive rabbit hole world of sci-fi fanzines, containing letters from fans squabbling back and forth, convention reports, and book/film reviews. The world of the sci-fi fanatic is a consistently unique view from the frontlines, often of confrontationally erudite perspective. He then led us through the comic books, and while not a huge area of personal interest for me, it was here he mentioned that UCR’s own Professor John Jennings had recently won a Hugo Award for his graphic novel adaptation of Octavia Butler’s Kindred, giving further indication of the campus’s fostering of sci-fi culture and talent.

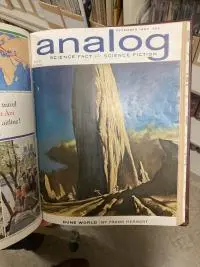

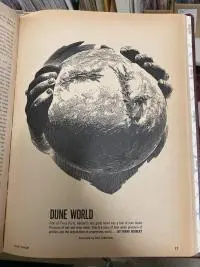

Next came the pulp periodicals — Amazing Stories, Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Galaxy, and the like. In addition to the original issues, Andrew showed us some pulps converted into library bindings, a sturdier preservation method since the low-quality paper of the original pulps disintegrated easily. We saw the original Dune, which appeared in serialized form in the December 1963 - February 1964 issues of Analog, under the name Dune World; followed by Prophet of Dune (Jan-May 1965), all illustrated by John Schoenherr. For such a pillar of science fiction achievement, the Dune stories went largely overlooked upon their release — Andrew mentioned there was no immediate response among even the most enthusiastic fanzines, suggesting pulps equally exalted and buried great works; its vast, prolific frequency likely to jumble attention spans. “It just needed time,” said Andrew, “Because it ended up winning the Hugo award a year or two later.”

One of the more fascinating time-stamped pulp items Andrew showed us wasn’t a story, but an advertisement — dueling face-to-face paid advertisements listing science fiction authors who were pro-Vietnam war aside another list of anti-war authors. “The first thing that sort of jumped out at me here,” said Andrew, “Is that the authors who were opposed to the war were a sort of who’s who of the Sci Fi New Wave.”

“Right,” I concurred. “Because guys like Harlan Ellison aimed to bury those dinosaurs behind them, that old fashioned mentality.”

The story Andrew was able to glean from the dueling ads: when the conservative sci-fi author Poul Anderson found out about an anti-war petition circulating the conventions, he felt it couldn’t go uncontested. “From what I could discern, it wasn’t that Anderson was super hawkish, it’s just some on the pro-war side felt we had a responsibility to the people of Vietnam to stay there and help them,” he explained. “Though others were complete right-wing hawks — your Edward Hamiltons, your Robert Heinleins, your Larry Nivens…”

We followed Andrew to the Star Trek section, unveiling rare and impeccably detailed behind-the-scenes items from the 60s TV show: original scripts, story boards, call sheets, shot lists, etc. Keeping with the visual theme, we visited the section of writer/visual artist Morris Scott Dollens, whose work graced countless sci-fi books and magazines, inside and out. His early fanzines employed hectography, a method which allowed different colored layers to be printed over one another, which lent to Dollens’s bold, striking style. Andrew showed some of his original sketchbooks, containing 3” watercolor studies of various alien landscapes.

In another aisle, Andrew picked up a World Fantasy Award, featuring the stylized sculpture of a familiar face. “So, this is the head of H.P. Lovecraft, which eventually led to quite the controversy among the WFA,” he said. “Due to Lovecraft’s overt racism and sexism, women and people of color were offended by receiving this award — like, ‘why do I have a bust of a horrible bigot?’ They were embarrassed to show the awards to people, so they began speaking out.” The protests would eventually remove Lovecraft’s likeness from the award to a more evocative symbol of the genre, a seductive full moon behind a gnarled leafless tree. Andrew and I briefly poked fun at Lovecraft’s overdone, tiresome prose; an element that didn’t exactly age well either. “There was a reason why he was obscure for his own time — people just couldn’t take him seriously.”

We were shown an angry, lengthy correspondence from Stephen King to writer/historian/critic Fred Patten, who, while giving The Shining a good review, included one passage in which he states that “King overdoes it,” insisting the novel goes on for far too long. King spends two typed out pages disassembling Patten’s statement, from a period when he had more time to obsess over a lukewarm review. “… I feel the novelist should be given all the rope he needs… If he chooses to hang himself with that rope, that is his business,” King wrote.

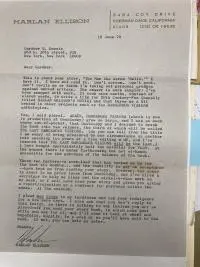

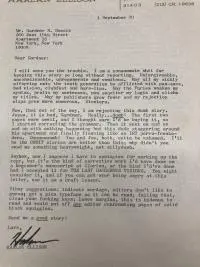

I told Andrew what a huge Harlan Ellison fan I am — and he proudly showed off a series of two essential Ellison letters to the writer/editor Gardner Dozois (fifteen-time winner of the Hugo Award for Best Editing, mind you). The first, a four paragraph long over-explanation why Ellison had yet to read Gardener’s story submission. This gives us a glimpse into Ellison’s twisted Golden Rule ethics; in this case, his refusal to leave a hard-working writer hanging, that though Ellison had yet to deliver an answer, he was thinking about him but not without the insistence that his time is also precious. “I plead mea culpa to my tardiness and ask your indulgence for a few more days,” wrote Ellison. “I also ask that you don’t reply to this letter, as there is nothing to say (unless you are so pissed off and want your story back…).” The second letter contained the dreaded verdict, a classic irreverent Ellison rejection, full of both scholarly and juvenile insult, if not straight-up abuse. “… I am rejecting this dumb story. Jesus, it is bad, Gardner. Really… dumb!... Duuuuuuuumb! Why didn’t you send me something heavy weight, not sillydumb? You outta be ashamed.”

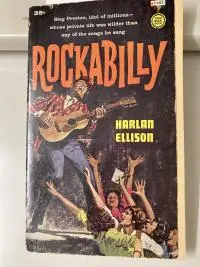

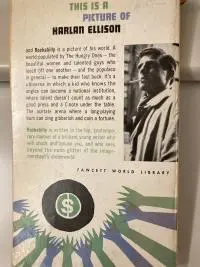

While on the subject of Ellison, I asked Andrew if the Eaton has one of my bucket list items, something I’ve always wanted to see and hold: The first edition of Ellison’s Spider Kiss novel, under its original title, Rockabilly. Before Ellison began writing sci-fi and speculative fiction, he wrote strong juvenile delinquent pulp. The novel Rockabilly was his foray into the rock n’ roll fable, a story that exposed how the sausage is made, the corruption of the music PR machine and the bad behaviors it encouraged for record sales. After Andrew did some searching, he found it, much to my hard to contain overjoy. The book looks like any other pulp trash novel from that era, unaware of the prophetic, intelligent critic of youth culture exploitation it contained. This was the fate of countless essential works at that time: buried in the crudity of reductionist marketing. While not sci-fi, the story is definitely a speculative fiction, pondering what might happen to a Jerry Lee Lewis inspired character pushed to the absolute limits of his “killer” behavior.

Before we’d conclude Andrew’s friendly, informative two-hour tour of the Eaton Library, we’d gaze at the 50 Books x 50 Years wall, commemorating The Eaton’s exhibit where they chose one landmark sci-fi/fantasy book for every year of the last half-century. Since the Eaton is a closed-stacks facility (where you can’t browse – only request items and read on site), we weren’t able to leave with anything, but our minds and hearts were over-brimming, our hands fully absorbent with the residue of enchantment.

Get The Spring at Bookshop or Amazon

Get Spider Kiss at Amazon

About the author

Gabriel Hart lives in Morongo Valley in California’s High Desert. His literary-pulp collection Fallout From Our Asphalt Hell is out now from Close to the Bone (U.K.). He's the author of Palm Springs noir novelette A Return To Spring (2020, Mannison Press), the dispo-pocalyptic twin-novel Virgins In Reverse / The Intrusion (2019, Traveling Shoes Press), and his debut poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1. Other works can be found at ExPat Press, Misery Tourism, Joyless House, Shotgun Honey, Bristol Noir, Crime Poetry Weekly, and Punk Noir. He's a monthly columnist for Lit Reactor and a regular contributor to Los Angeles Review of Books.