Satire has long been part of the realm of the newspaper comic strip, and none do it better than Garry Trudeau and his long-running Doonesbury. Created during the height of ‘60s and ‘70s counterculture when Trudeau was in college, its approach to politics is decidedly liberal and unabashedly tongue-in-cheek. The only problem is these days the lines between the situations depicted in the comic strip and reality have started to blur. People have seemingly lost the ability to tell the difference between real news and what’s come to be known as “fake news.” And a big part of this is because the Internet has created such a ubiquity of information that it’s hard to parse out what’s real anymore.

It wasn’t always this way. Satire was once wielded as a powerful weapon to bring down opponents, including governments, and effect social change. Going back 300 years, this has never been more true than with Jonathan Swift.

Swift was born on November 30, 1667, and accomplished many things in his life. He was an Irish cleric, political pamphleteer, poet and writer best known for Gulliver’s Travels (1726) and A Modest Proposal (1729). With the former he also ventured into satirical territory, taking aim at the state of the European government at the time and also petty differences between religions.

The latter, an essay whose full title is A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People from being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and For Making them Beneficial to the Publick, is considered to be an example of early modern Western satire. Swift published it anonymously at the time as it suggests that the impoverished Irish might ease their economic troubles by selling their children as food for rich gentlemen and ladies.

For the last 300 years this has been a staple of satire, with the title “A Modest Proposal” becoming shorthand for anyone wanting to make a straight-faced takedown of a subject. I even discussed it once before in an article talking about “A Modest Proposal: Don’t Make English Official, Ban It Instead”. Written by Dennis Baron and published in 1996 in The Washington Post, it tackles a topic that comes up on occasion, of Congress deciding whether or not the United States should have an official language, by going to the other extreme. Baron highlights the absurdity of the argument by pointing out the history of other similar practices and how it would be executed.

The problem is when I’ve taught this article in the classroom most students don’t understand that it’s satire, or even the definition of satire. They took the article at face value, and some even argued it was a good idea. And that was my first exposure to Poe’s Law.

Poe’s Law started with the idea that on the Internet, without a clear indicator of the author’s intent, it is impossible to create a parody of extreme views so obviously exaggerated that it cannot be mistaken by some readers or viewers as a sincere expression of the parodied views. The original statement was made by Nathan Poe, in which he said, “Without a winking smiley or other blatant display of humor, it is utterly impossible to parody a Creationist in such a way that someone won’t mistake for the genuine article.”

Poe said this on an Internet forum about Christianity in 2005, hence the reference to Creationists. Ever since then it’s come to encompass discussion in general on the Internet. And a dozen years later this concept is more relevant than ever.

A Wired.com article by Emma Grey Ellis from June of this year puts it well:

If you’ve spent much time on social media, you’ve seen this tactic before: someone trying to slip out of their rhetorical bind by claiming that their offending statement had been a joke, and that you’re just being hypersensitive. That thing where someone wears irony as a defense, hiding their true motives? What is that?

That, friend, is Poe’s Law: On the internet, it’s impossible to tell who is joking. In other words, it’s the thinking person’s ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. But Poe’s Law isn’t only useful as a defense against pearl-clutching reactions. It’s also a diagnosis of exactly how the troll mentality has weakened internet culture. If nobody knows what anyone means, then every denial is plausible.

And one could argue that the phrase “a modest proposal” works in a very similar way to the winking smiley, as Poe puts it above. In learned circles, putting that phrase in the title was once a dead giveaway that the content of the following text, however subtle, was satire. This wasn’t necessary in Swift’s original text because the treatise itself, with its over-the-top suggestion of selling Irish children for food, was enough of a signifier. But it's easy to imagine that if Swift was alive today and presented his proposal as an op-ed for, say, Slate, there would be many a people on Facebook and Twitter sharing it with praises and likes.

That's the world of 2017. Regardless of one’s political views or approval of the man, a reality star is currently president of the United States of America. And on Wednesday, May 31, 2017, this man sent out a tweet with the word “covfefe” in it, and then refused to admit it was a typo. You can’t make this stuff up.

Donald Trump has been a divisive figure for more than 30 years, and has been a source of satire that up until 2016 was meant as a way of subverting him. In a 1990 episode of The Simpsons, it was a joke that he would someday be president. The screenwriter of Back to the Future Part II has admitted in recent years that in the 1989 movie Biff Tannen’s takeover of the city of Hill Valley, turning it into a Las Vegas-esque dystopia, was based on the Trump. And, of course, there’s Doonesbury.

Doonesbury is a comic strip by American cartoonist Garry Trudeau, who self-identified in a 2016 Washington Post article as a member of the “ridicule industry,” that chronicles the adventures and lives of an eclectic cast, from the President of the United States to the title character, Michael Doonesbury, starting with him as a college student. It began as Bull Tales in 1968 when Trudeau was at Yale University, with the focus on campus life, and went into syndication in 1970 as Doonesbury. Since then it has acted as a social and political commentary, often featuring real-life people in hyperbolic roles. This has included over the years gonzo reporter Hunter S. Thompson, immortalized as the fictionalized character Uncle Duke, who ironically wrote a letter published in Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist, against the Vietnam War that used A Modest Proposal’s satire technique. Trudea’s jokes have also been made at the expense of the man himself, Donald J. Trump.

On September 2, 1987, a little over 30 years ago from this very day, Trump spent nearly $100,000 to place a full-page advertisement criticizing U.S. foreign policy in the New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Boston Globe. The letter said that “the world is laughing at American politicians.” Trump was already floating the idea of running for office at the time. “I believe that if I did run for president, I’d win,” he told the New York Times that November, although he denied he would run.

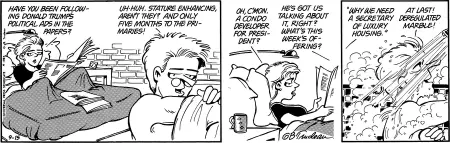

Trudeau naturally responded. On September 14, he featured a comic strip in which an interviewee is being asked about Ev Mecham, who was then running for governor of Arizona. The man says, “The guy comes across as an ignorant bigot. He makes insane appointments. He’s losing the state millions in business…I mean when you think about it, is there anyone less suited for high office than Ev Mecham?” To which, in the following panel, Doonesbury thinks, “Donald Trump?” while watching TV. Then the following day Doonesbury muses in the shower, “He’s got us talking about it, right?” referring to running for president. “What’s this week’s offering?" "Why we need a secretary of luxury housing." "At last, deregulated marble!” And last year these two strips and many more were all collected in one book titled Yuge! 30 Years of Doonesbury on Trump.

What brought America to this point where everything and nothing is a joke? There’s a sense of bothsidesism and whataboutery that permeates modern humor, and mostly this is reflected in the likes of South Park and Family Guy. South Park started in 1997 and Family Guy started in 1998, and over the years both shows have been known for their shocking and outrageous jokes that push the envelope. The key to getting away with this for both shows has been to target everyone. So it’s okay to make anti-semitic, homophobic, racist and sexist jokes as long as they’re lampshaded, usually when a character within the show calls out the joke.

But if everything can be made fun of then no one really stands for or believes in anything anymore. Jonathan Swift's entire modus operandi was predicated on people picking up context clues and realizing that a line has to exist for it to be crossed. Doonesbury knows that a joke can be even funnier when it’s tinged with an element of truth. But in the age of Poe’s Law, everything has become prismatic. The old saying that the truth is stranger than fiction has been writ large, and it’s hard to know whether it’s more appropriate to laugh or to cry.

About the author

A professor once told Bart Bishop that all literature is about "sex, death and religion," tainting his mind forever. A Master's in English later, he teaches college writing and tells his students the same thing, constantly, much to their chagrin. He’s also edited two published novels and loves overthinking movies, books, the theater and fiction in all forms at such varied spots as CHUD, Bleeding Cool, CityBeat and Cincinnati Magazine. He lives in Cincinnati, Ohio with his wife and daughter.