Photo by Jill Krementz

You might have read this article recently from the author Catherine Nicols who discovered that interest in her queries to agents increased eight fold when she pretended to be a man instead of a woman. While this is the kind of reflexive male-favouring that we were all promised would become a thing of the past about three decades ago and could well fill you with the kind of rage that makes a person run to the nearest bookshop and set fire to all the books written by men, you should put that box of matches and accelerant back in the drawer (for now) and read on. The publishing industry might still give the impression that the best form of writing implement is a penis dipped in ink, but for centuries the movers and shakers in the world of books have been women. Especially these ones:

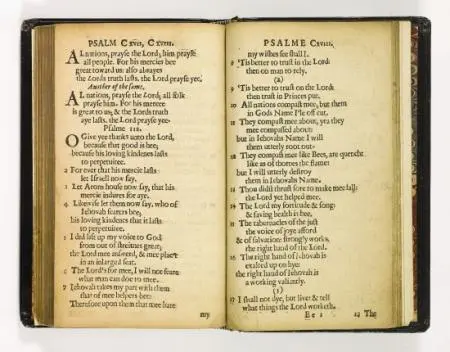

Elizabeth Harris Glover – the First American Publisher

Glover travelled from Britain to the New World in 1638, along with her husband, Jose, their children and a printing press. During the voyage Jose died, but undeterred by widowhood, a new country and trying to look after five kids on her own, Elizabeth stuck to the original plan and set up a printing business upon her arrival in Massachusetts.

We don’t know much about Glover but she must have been a powerhouse. The English Colonies were at that point all of two decades old and most of the settlers were fully occupied trying to find enough to eat and running away from bears. You could have forgiven Glover for immediately turning the printing press into firewood and devoting herself to growing food for her family, but she didn’t. Instead she applied for a license to run a business (women needed special permission to enter into commerce back then), found an assistant to help her run the machinery and got started. During Glover’s ownership the company produced 1700 copies of the Bay Psalm Book, the first book to be printed in the English colonies. The press now stands in the Library of Congress and 11 copies of the original psalm book still exist.

Yeah yeah but how did she change the face of publishing?

There are plenty of copies of the Bible around, right? So Glover’s achievement might not seem that profound. Someone would have started up a printing company eventually, you might say. The fact a woman got there first is coincidental.

Which is fair comment except for one fact: Glover called her company the Cambridge Press, after the town she settled in and eventually the business was taken over by the local college. Harvard College. Yes, Harvard University Press, publisher of Stephen Jay Gould, Eudora Welty, Martha Nussbaum and Thomas Piketty, was founded by a woman.

Harriet Shaw Weaver – Champion of Modernism

Joyce, never a man who enjoyed a conventional existence, left Dublin in 1904 with his girlfriend Nora Barnacle to work as a teacher of English in Austria. He hoped eventually to earn a living as a writer, but in the meantime took a job with Berlitz teaching English to foreigners. He thought this would be temporary. He thought he’d get a book deal soon.

A decade later, Joyce was still teaching English. He had sold one book, Dubliners, which he had submitted eighteen times to fifteen different publishers. At one point, Joyce had rescued his manuscript from immolation when the printers setting the plates became outraged at the content. By 1914, discouraged and ten years older than when he started, it didn’t look like literary success for Joyce was just around the corner. It looked like literary success had disappeared to a remote South Sea island where it was partying snootily with George Bernard Shaw and Henry James.

Ezra Pound, facilitator extraordinaire, sent the first chapter of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man to Weaver, who edited and ran a literary magazine called The Egoist. Unlike the Irish printers, Weaver did not set fire to Joyce’s manuscript. Instead she serialized it, then became Joyce’s patron, helping him out financially so he could give up teaching and devote himself to writing.

Yeah yeah but how did she change the face of publishing?

It’s easy to underestimate how big a challenge Weaver faced in getting Joyce’s work into print. She had money. All she needed to do was find a printing company and wave her chequebook at them, right?

It wasn’t that simple. No business would agree to take the work. Weaver had to set up her own press to print and distribute Portrait and attitudes had not softened when Joyce finished his second novel Ulysses. Weaver took the manuscript to Paris when again no English language publisher would touch it, where Sylvia Beach, owner of the bookshop and library Shakespeare and Company, produced it.

Without Weaver and to a lesser extent Beach, Joyce’s work would never have seen the light of day and the modernist movement would have lost a primary driving force.

Virginia Woolf – Transforming Our Concept of the Novel

But what did Virginia Woolf think of Joyce? Here’s what she wrote in her diary about her reaction to the first few chapters of Ulysses:

An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking, & ultimately nauseating. When one can have cooked flesh, why have the raw?

She gave up at page 200, which is probably further than most of us get with Joyce’s monstrously epic work. At that time, Woolf was at work on Mrs Dalloway, her fourth novel, eventually published in 1925, which she followed with To the Lighthouse in 1927. Both of these books employ the stream of consciousness technique: Dalloway follows the course of one day in the life of a woman planning a party. To the Lighthouse, more ambitious in scope, focuses on the Ramsay family and their trips to a cottage on the Isle of Skye. Both books are now regarded as classics.

She gave up at page 200, which is probably further than most of us get with Joyce’s monstrously epic work. At that time, Woolf was at work on Mrs Dalloway, her fourth novel, eventually published in 1925, which she followed with To the Lighthouse in 1927. Both of these books employ the stream of consciousness technique: Dalloway follows the course of one day in the life of a woman planning a party. To the Lighthouse, more ambitious in scope, focuses on the Ramsay family and their trips to a cottage on the Isle of Skye. Both books are now regarded as classics.

When she wasn’t writing ground breaking fiction, Woolf set up the Hogarth Press with her husband Leonard, fundamentally influenced British culture with the Bloomsbury Group, had an affair with Vita Sackville West, battled with bipolar disorder and dealt with the aftermath of childhood sexual abuse. As Jeanette Winterson said about her work:

There is no warm blanket to be had out of Virginia Woolf; there is wind and sun and you naked. It is not remoteness of feeling in Woolf, it is excess; the unbearable quiver of nerves and the heart pounding. It is exposure.

Yeah yeah but how did she change the face of publishing?

What Joyce started, Woolf finished. She cooked the meat Joyce left raw. Joyce smashed the prevailing notions about what fiction ought to be; ideas that hadn’t changed very much since the days of Ancient Greece: three acts, dramatic arcs, beginnings, middles and ends. Woolf picked up the pieces Joyce left scattered on the floor and patiently rearranged them into something coherent. She tells her stories entirely from within her characters; you as a reader have no omniscient narrator to guide you through the story (still a central feature of most fiction). You have to create the story for yourself, from the disparate thoughts and observations of the people within it. It’s a complicated, demanding, ultimately rewarding process. Read Woolf and you begin to see how unlimited the possibilities of fiction can be.

Joan Didion – Inventor of Literary Journalism

It’s hard to credit this now in today’s world of bestselling authors like Krakauer, Strayed and Klein, but a few decades ago nobody rated non-fiction as real literature. No one reviewed it. No one critiqued it. Telling a true story instead of a made-up one had the same significance in literary terms as a flake of dandruff on the shoulder of Charles Dickens’ second best suit.

Into this myopic scene strolled Joan Didion. Didion had been working as a journalist and feature writer since the early 1960s, publishing mainly in the Saturday Evening Post. In 1968 Farrar Strauss and Giroux published a collection of her articles under the title Slouching Towards Bethlehem and instead of suffering the usual non-fiction fate of ending up in the great dustpan of Things That Are Not Really Literature, the book took off. In The New York Time Book Review, Dan Wakefield called it ‘a rich display of some of the best prose written today in this country’ and with that the Rubicon was crossed and New Journalism was born. It became respectable in non-fiction to write first person accounts, to use literary techniques, to even include the occasional adjective. In short non-fiction became Non-Fiction and Didion became its queen, continuing to shift the boundary of what counts as literature with another collection of essays: The White Album and later The Year of Magical Thinking, an account of a devastating year in her life which turned simple memoir into an art form.

Yeah yeah but how did she change the face of publishing?

We tell ourselves stories in order to live Didion says in the first sentence of The White Album and she’s right, we do. But if we limit ourselves to the stories we invent and ignore the ones which have really happened, then we lose half of that life-sustaining narrative. Didion allowed publishing to take non-fiction seriously and opened the way for an entire genre to develop. Where she led many others have followed.

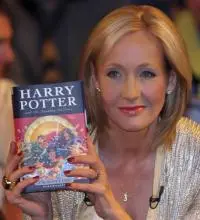

J.K. Rowling – Going Global

Probably the best story to come out of the Rowling myth canon – better than the writing-in-cafes, living-on-benefits, rejected-by-every-publisher-on-the-planet-and-some-from-other-galaxies anecdotes with which we are all familiar – is this one. Bloomsbury editor Barry Cunningham, who gave Rowling her first advance of £1500 for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone also gave her a piece of advice. Don’t give up the day job he said (Rowling was at that time training to be a teacher). Writing children’s books never pays.

400 million copies later, Harry Potter holds the title of the best-selling book series ever. Possibly there are inhabitants of some far flung planet who have not heard of Rowling’s books, but I wouldn’t count on it. The series is available in 65 languages, has spawned a movie series, toys, video games and two visitor attractions. A stage play is in the works. Rowling says she has ‘plenty of money but is not a billionaire’. Forbes agrees. Apparently she gives too much to charity to qualify for its list.

400 million copies later, Harry Potter holds the title of the best-selling book series ever. Possibly there are inhabitants of some far flung planet who have not heard of Rowling’s books, but I wouldn’t count on it. The series is available in 65 languages, has spawned a movie series, toys, video games and two visitor attractions. A stage play is in the works. Rowling says she has ‘plenty of money but is not a billionaire’. Forbes agrees. Apparently she gives too much to charity to qualify for its list.

Yeah yeah but how did she change the face of publishing?

Potter forced publishing, innocent but eager to learn, out of its booklined comfort zone and into the rough yet experienced arms of global commerce. Rowling, who retained artistic control of her creation, has proved a competent midwife to what has now developed into a megabrand. With her input, the movies are not only well-crafted and enjoyable, they have also supported the British film industry (she made it a condition that they be shot in the UK and feature only British actors). The Potter phenomenon opened the door to books as brand, expanding the role of literature from provider of words to provider of characters you love and want all over your dinnerware and bedlinen.

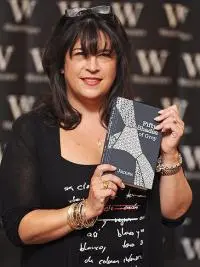

E.L. James – Making the Unacceptable Acceptable

We might mock her for her prose and for giving Christian Grey a penis which talks, but E.L. James, creator of the Fifty Shades series deserves a place in this list. She started writing in 2009, producing fan fiction which, like many thousands of others, she based on the Twilight series. With one wrinkle - James’ fan fiction involved BDSM.

This exposure of the whole dominance-submission subtext between Bella and Edward seemed to throw all who read the work into a frenzy. The numbers encouraged James. She self-published with a tiny Australian outfit, then as the numbers continued to climb, cinched a deal with Random House. You know the rest: stellar sales, film deals, conquering the planet. Like Rowling, James retained creative control of her product. She’s going to write and direct the next film. A second book written from the perspective of Christian Grey will probably form her next project.

This exposure of the whole dominance-submission subtext between Bella and Edward seemed to throw all who read the work into a frenzy. The numbers encouraged James. She self-published with a tiny Australian outfit, then as the numbers continued to climb, cinched a deal with Random House. You know the rest: stellar sales, film deals, conquering the planet. Like Rowling, James retained creative control of her product. She’s going to write and direct the next film. A second book written from the perspective of Christian Grey will probably form her next project.

Yeah yeah but how did she change the face of publishing?

For all the flapdoodling about Fifty Shades endorsing abusive relationships and/or irredeemably corrupting all who read it, the series made sex in books acceptable. Fifty Shades might hold the prize as the book most likely to be left behind in hotel rooms, but reading a copy on the commute into work will hardly raise an eyebrow. Publishing, which can tend towards the stuffy, post-Fifty Shades has every excuse to pop its top button and revel in a new age of permissiveness.

If these women and their achievements form a theme, it’s that for all the men getting most of the attention, in publishing the women make more than their fair share of the innovations. Women brought publishing to America, facilitated and then perfected modernism, reinvented non-fiction, created the first global literary brand, and made spanking an acceptable and highly lucrative plot device. Catherine Nicols might have discovered that a gender switch made her more attractive to agents, but I prefer to follow in the footsteps of Didion et al and stick to being a woman.

About the author

Cath Murphy is Review Editor at LitReactor.com and cohost of the Unprintable podcast. Together with the fabulous Eve Harvey she also talks about slightly naughty stuff at the Domestic Hell blog and podcast.

Three words to describe Cath: mature, irresponsible, contradictory, unreliable...oh...that's four.