[Image's facepalm shot courtesy of Striatic.]

You want to write better dialogue. You've learned a few tricks of the trade. Great work so far, but are you unwittingly sabotaging your work, leaving only stilted, one-dimensional dialogue for your readers? Here are six painfully common ways writers botch their dialogue.

1. These voices are all clones.

[Image courtesy of HJ Media Studios]

As writers develop, they learn to write dialogue that shows off each character's personality. Often, the process begins with figuring out how to showcase one personality trait on the page. Have you spotted the problem? Having learned just one personality type, this "strength" of dialogue often become contagious and infects every character who ever speaks.

A good example of this is the film Easy A. While it's easy enough to praise the witty dialogue, it's difficult to buy in to that dialogue when every character lets loose snappy one-liners and shows an astoundingly similar sense of humor. What would be a strength in a single character becomes a clone army of wit that sabotages the dialogue's believability.

2. Long lines of linear dialogue.

Yesterday morning I was chatting with my dad. "First, I wanted to thank you for inviting me on that camp out. I had fun." "Good," said my dad. "I'm glad you enjoyed it." There was a dead pause. I hesitated, uncertain why he was looking at me with expectation. "... and second?" he asked.

It took me all of one sentence to lose my train of thought and forget items two, three, and four. These side-tracks and slip-ups happen to everyone, regularly, and much of real-world dialogue involves getting back on track. Underdeveloped dialogue, on the other hand, often approaches conversation as if there's a clear linear structure whereby all characters can directly and effectively communicate their points.

Remember, dialogue isn't only being used to communicate what the characters want to communicate: it also shows each character's emotional state, creates a sense of realism, subtly hints at how characters perceive themselves and each other, and so on. Beyond helping your dialogue feel more organic, side-tracks can develop your characters and build a believable world.

3. Everyone's so damn proper.

As a writer, chances are you've got a healthy vocabulary and a strong sense of "proper" language. You speak like a professor, you understand good grammar, you can structure sentences perfectly, and your mother and I are very proud of you. You're also probably smart enough to see where I'm going with this: Just because you have a tumescent vocabulary and a strong sense of language doesn't mean your characters will share these traits.

Some of the common blunders in this category include:

- The use of vocabulary that extends beyond the apparent intelligence or education of the character.

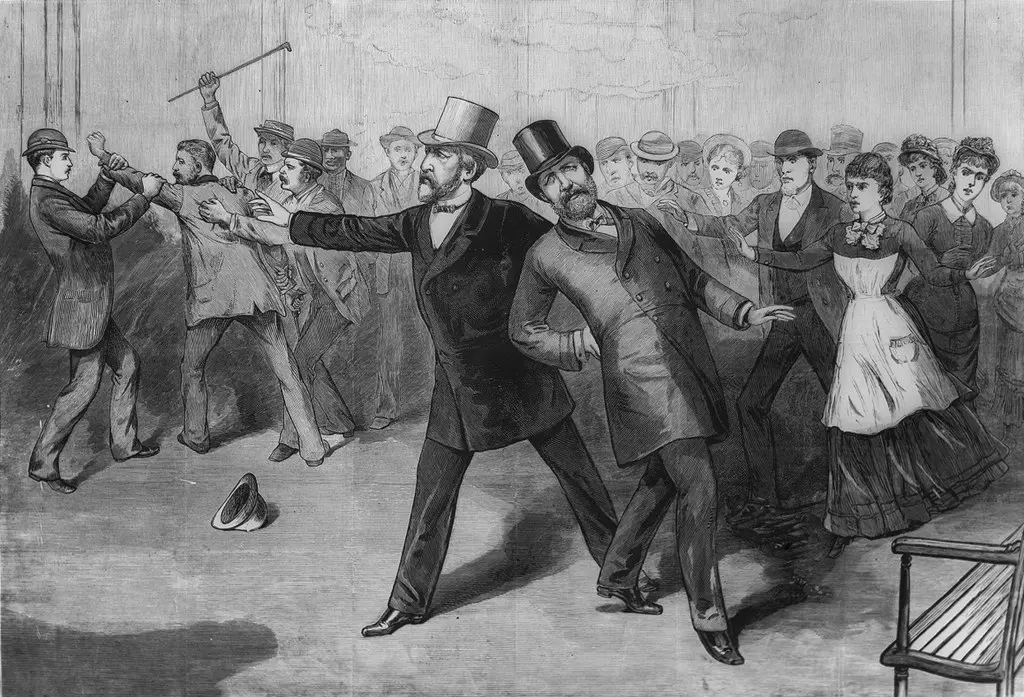

- A lack of contractions (which makes everyone seem like they're attending an 19th-century top-hat party).

- Every character being able to express themselves with eloquence, including an ability to richly describe sensory details.

- Everyone using perfect grammar and syntax.

You should still take care to ensure that the dialogue is comprehensible and enjoyable; however, in the end, your average character should talk like an average person—not like a seasoned writer.

4. You're really sure of that, are you?

Authors have the opportunity to play God by building worlds and determining the fate of each character; the God complex is part of why we write, isn't it? But sometimes that God-like awareness and certainty creeps into the psyche of characters, and they speak without hesitance or self-doubt. Yet if you listen to real-world dialogue, it won't take long to notice how often people are uncertain and noncommittal. Hesitance and uncertainty are important parts of how most people talk.

It's not just that we qualify our statements. Often, people try to make statements of certainty but can't quite pull away from the ingrained linguistic habit of uncertainty. Referring to an upcoming trip to Yellowstone, a friend of mine said, "We'll probably definitely see at least one black bear." Probably definitely. I stopped myself from quoting Anchorman's "60% of the time it works every time."

While there are real-world exceptions who come off as sure about everything, who are bastions of ethical certainty, etc., you're just as likely to find the opposite: People who are never certain about, never commit to anything. If you've written one character who is certain and concrete about everything, that's probably fine. Generally speaking, though, your characters will (probably definitely) feel more realistic if they're a touch more hesitant in what they say, how they say it, and what they feel overall.

5. Expository dialogue is expository.

Revealing your plot and back-story through dialogue is, in many cases, strongly preferable to presenting plot elements through direct exposition. However, these revelations must be made gently and with care.

As one example, a student I was workshopping with in an intro to creative writing course had a complex short story with a great deal of back-story. In an opening scene, the principal tells the protagonist, "You've been having a hard time. Your mother died a week ago." Which did its job in revealing the back-story, but isn't something that a person will typically tell someone who just lost their mother. I was reminded of this exchange from Garden State:

"Largeman? Holy shit! Aw, man, how you doin'?"

"I'm ... I'm great!"

"Your mom just died!"

"I know!"

In the case of Garden State, the unrealistic quality of telling someone their own back-story and motives is exploited to humorous effect. Sadly, most writers aren't aware when they're providing exposition like this, and the results are stilted, uncomfortable, and funny in all the ways writers don't want their work to be funny.

6. Why is everyone being so nice?

When people speak, they are giving subtle signals about social power dynamics. These can include the direct concerns of "who's in charge," as well as questions of how characters perceive their relationship with others. I've seen more than a handful of writers prevent these dynamics from showing at all by writing every character as being imperviously nice and respectful, no matter who the character is talking to.

The other common tendency here is to have all main characters remain relentlessly sarcastic and withdrawn, no matter what. Either of these approaches will make dialogue feel one-dimensional. Beyond asking yourself who a character is and how they would communicate a specific idea, ask how they would communicate that idea in context. Even if they're a nice person, they're going to answer the question, "Where did you get that bong?" differently based on whether they're responding to their friend, lover, mother, or a police officer.

It can be difficult to write organic dialogue that moves the story forward and develops characters effectively. The most important things you can do are hunt out work with well-written dialogue and keep writing dialogue yourself. You'll write a great many bad conversations before you write any good ones. Still, by being aware of these six common ways writers botch their dialogue, you can give yourself a heads-up and a head start.

About the author

Rob is a writer and educator. He is intensely ADD, obsessive about his passions, and enjoys a good gin and tonic. Check out his website for multiple web fiction projects, author interviews, and various resources for writers.