Images via Jeshoots and rawpixel

I’ve been playing video games about as long as I’ve been a writer, and for several years I was in the game industry — as a tester, designer, and writer.

Many of the fiction writers I know don’t play games, especially those from an older generation, and often look at them with disdain — like they’ll rot your brain and give you rickets. But games have evolved a lot since the days of Pac-Man and even the original Mortal Kombat, and are now more complex, engaging, and narrative rich than ever. They can do things that may change your perspective on your fiction, and offer a richer palette of experience to draw from.

And if you like games and just needed an excuse to play more, here it is.

Error is the Best Learning Mechanism

A game is often defined as a structured form of play with rules. And in my opinion, in order for a game to truly be a game, it must have a fail state. In order for a win to matter, there must be a way to lose. Otherwise there's no challenge. No reason to struggle. No feeling of accomplishment.

Franchises like Dark Souls were designed so you could die. A lot. The appeal of the game is mostly how challenging it is to complete. Other games, like Stardew Valley, don't have fail conditions per se, but there are more and less optimal ways to play. (Some may even argue it isn't a real game, but a 'simulator'.)

When you first start out playing a game, you are probably going to be bad at it. You don't understand how the controls work. Don't know best strategies. What paths to take. There are hundreds, probably thousands of hours of video on Youtube on how to improve your skill on League of Legends. And oftentimes when you're playing a particularly difficult sequence in a game, the fun yields to frustration. You feel like quitting. Maybe yelling at the game.

But if you push through that feeling, you get to the other side. You keep going. The frustration gives way to satisfaction. And you'll often find that there's nothing you can't do if you put enough time into learning the mechanisms.

To think of error as something that can be avoided is an error itself. It should not be thought of as a failure.

So it is with writing.

Work through the frustration when you get stuck. Don't berate yourself for "failing" when you write something that isn't landing. This is just part of the game, and the only way to fail is to stop playing. Yes, it sucks to write 3000 words and then realize you can't use any of them, or realize you need to shelve a story because it's not conveying the message you intended. But you had to get there to realize it wasn't working. You could not have achieved a success state without a fail state.

If you start thinking of it as part of the process, it will stop hurting so much. Failure is the way these things work.

And if you couldn't fail, it wouldn't feel so good when you succeeded.

The Medium is the Message

Video games are the medium of interaction. They are different from every other kind of art in that sense. There can be art installations that are interactive, or video games that are art — but each has an intrinsic core that if removed, would make it something else. Without being able to interact, a game would cease to be a game.

Like every piece of art, a game tells a story. Story seems to be the thread that runs through every human medium.

The best game designers understand that the story of a game should be told via interaction iself. An excellent example of this is the Japanese designer Fumito Ueda, who created Ico, The Shadow of The Colossus, and The Last Guardian. There is almost no dialog in these games, and the stories are told via the happenings in the game.

In Ico, a boy with horns is left to die in an abandoned fortress, where he meets the queen's captive daughter, a young woman named Yorda. During combat Ico must protect Yorda or she'll be captured by shadow enemies and dragged to a portal in the ground, thus ending the game. Ico must also hold her hand as they walk along exploring the fortress, and if he leaves her for too long without supervision, shadows will come and drag her way. The idea that Ico must protect Yorda is thus not created by dialog, but by the mechanics of the game itself.

Every element of the game — the animation, atmosphere, art, music, combat, and controls — come together to create a story that could not have been told via any other medium.

Contrast this to a game like Last of Us, a critically acclaimed game that basically thinks it's a movie. While it has great dialog and art, most of the story is told via cut-scenes, and the gameplay itself is incredibly basic. Sneak around, kill zombies, place ladders to get to other places where you can place another ladder. Don't get me wrong, The Last of Us is a good video-game. But I think it falls short of being a masterpiece, because instead of using the medium of a game to tell its story, it relies on fallbacks like cinematic cut-scenes at most of its pivotal moments.

It's important to remember when writing books, that you are not creating a painting, a movie, or a game. You are relaying a narrative via text. Too often writers will try to create a story like they are describing a movie, and it shows. The text is sparse. They set up a "shot" by describing everything in the background. The "camera" of the POV is zoomed out, so we never get a glimpse into the character.

I think this comes from a fundamental misunderstanding that the story itself is all that's important, not the package it comes in. Text is not just an inconvenient vehicle for your vision. It is a part of the narrative itself.

Writing fiction does things that other mediums cannot. So if you want to create a masterpiece and not just a second-rate movie made out of text, you have to utilize the medium itself.

When you are writing: experiment. Play with text. See how certain words leave different flavors on the page. See how shaping the paragraphs changes the meaning. Explore the rhythm of sentences. Use more specific words to see how they subtly change the image left in your mind.

Change the Background, Change The Scene

Back when I first started playing games in the 90s, it seemed like every game on a console followed the same formula. There would be a forest level, a city level, an underwater level, an ice level (I hated the goddamn ice levels. Couldn't see a damn thing.), and a fire/volcano level. Now games tend to be more sophisticated in their level design, but it was a good way to keep things fresh. Game mechanics can often get repetitive, so it was important to switch up the backgrounds so you felt like you weren't doing the same thing over and over again. A great example of this kind of "old" game style is Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.

Of course, the best games don't just have different backgrounds, but different kinds of game content. However, creating new mechanical systems, with lots of coding hours, is often way more complicated and more expensive than just uploading several new art assets.

Resident Evil 7 is a good example of a more modern, "grown-up" kind of level design, (heavily taking inspiration from the defunct P.T.,) largely taking place in a single lot in the middle of a swamp, but with different levels that feel seamless, from a flooded basement to a garage with hanging bags of meat, to a house full of bugs, to a weird underground Saw-esque trap maze, that all make you feel like you're progressing and retain visual interest while maintaining a cogent theme.

This is related to writing because oftentimes I read stories that take place in the same gray, miasmic environment. Fights take place outside of bars. Existential crises take place inside of bars. People drive longingly past bars. You get the picture. Or I guess, the lack of one.

Even while reading plain text, we're visual creatures. We need stimuli to engage our minds in the story. A simple trick to keep people more engaged in your fiction is simply by creating different kinds of landscapes and environments for your characters to interact in. Instead of having an existential crisis in a bar, imagine if it was while parachuting, or in a canoe, or while hiding underneath a bed while the boyfriend of the girl you just slept with is hunting you down. And simply by moving the environment, the context changes, so that your fiction will feel more fresh and engaging as a result.

Think of it as a trick to allocating less mind resources while getting pretty much the same results: You're creating art assets, not building expensive code.

One great example of this is the game D4: Dark Dreams Don't Die, which features one of the most epic button-mashing brawls to take place on an airplane.

Humans love movement, even supposedly arbitrary movement. When things are moving, our eyes are drawn toward those things, because generally if something is moving, it can potentially kill you. That's the reason everyone stares if you decide to go running. Not because they're judging you (they probably are), but because our eyes can't help but be drawn to an object of interest. In fiction, this also implies.

People are more likely to pay attention if your character's declaration of love takes place while they're running from a giant prehistoric crocodile in a swamp vs. in yet another bar. That's just science.

Humanity is the X Factor: Multiplayer Games

I know, you're sick of hearing that characters are the most important part of fiction, but I swear this is a fresh take.

While I just talked about changing up the environment to maintain interest, some games do not take this approach. League of Legends is a MOBA (Multiplayer Online Battle Arena for you neophytes) where every match takes place on the same map. People log thousands upon thousands of hours in the same environment. It's probably one of the most addictive, most played games of all time. The League Championship Series gets more views than the super bowl. So what keeps the game from becoming boring?

For one, strategy becomes more important when novelty wears off, and everyone knows what everything is on the map. There are also tons of characters with different skills to master, and that means tons of different team compositions and ways to play.

But most importantly — it's the people. People are fighting against people in the arena, and it's the only element that changes every game. People rarely behave in the way you expect, and when you are grouped in teams of five, the combination of ways in which people can act are almost infinite. Games aren't sophisticated enough to change with enough variability to create endless content on their own. But people can do that.

From the game production side: It doesn't matter how many times Quality Assurance tests your game, how brilliant your designers are, or how much focus testing you do — when a game is released people will behave in unexpected ways, and play/interact with the game in ways the designers never intended. (For example, speed racing in Mario 64 or, on the darker side, money laundering via the mobile game Clash of Clans.)

(That's not to say people don't behave in patterns. Sometimes they behave in patterns that others refuse to understand or acknowledge, because they don't know enough about human nature. There is a universal rule when it comes to custom content that developers rarely acknowledged in the past: If you allow custom content in your game, people will find some way to create dicks.)

Playing a multiplayer game can be an interesting study in psychology and sociology, especially if you must work on teams to achieve a common goal. If most of your understanding of humanity is via movies or other kinds of fiction, your characters will probably be stale and wooden, and follow predictable paths that were designed to create Hollywood-style arcs. You need to experience how real people interact, deal with problems and solve them. A fast, easy way to do that without ever leaving your couch is via games. In such an environment you can see how people deal with crises and confrontation more often, even if it's simulated.

People exist outside the realm of fiction, outside the goals of plot, and every single one of us is the protagonist in our journey. Although there are patterns, people do not always follow rails, and there will always be those looking to break out of them.

Discover New Story Formulas

Not every journey is a hero's journey. The reason the hero's journey is so often repeated is because it is the universal story of self-actualization. You start out weak, become strong, and then defeat the monsters that are trying to destroy you. Everyone can relate to that, because it's the story everyone wants to have. Story formulas aren't just things bestselling writers "made up", they are resonant pieces of our psychology. A bestseller often becomes a bestseller because it has more resonant components than other stories.

Then Joseph Campbell identified the hero's journey, saw the recurring patterns, wrote a book about it, and gave every wannabe Tolkien an easy to follow guide for creating their own resonant stories. All well and good. We learn how to write better stories because of those who paved the way before us, and who identified patterns that could then be easily replicated.

But the hero's journey is just one of many stories. And I would argue there are story formulas that we have yet to identify. Some of the greatest stories of all time, like Taiko by Eiji Yoshikawa or War and Peace or A Game of Thrones are not only psychological stories, but sociological stories. Stories about large patterns, and how the psychological components intersect to create societies. And they have much more complex, moving parts than a hero's journey. (And as such, are more difficult to pull off.)

In order to create new stories, we often have to look to different mediums. There are plenty of video games that follow the hero's journey, but many of them do not. Games like Rollercoaster Tycoon and Sim City don't feature you controlling a single character, but acting as a God-like omniscient presence that creates a city or an amusement park.

Kenshi is a game where you start out as just another ordinary person, with no special powers or questlines, and you spend most of the first few hours getting the crap beaten out of you by wandering thugs. You can rise to power, not because you're ordained to it — but because you worked to get there.

Even with games that seem to have no possible story — like Tetris or Solitaire — the player creates a drama in their head, with highs, lows, stakes, and victories and defeats. We can’t help but see stories. We think in stories, because a story is just the contextualization of data. And it’s possible that games can help you learn to tell new stories, and reframe the way you think of plot formula.

Recommended Games For Writers

Okay, if I’ve convinced you to play some games to improve your fiction, here are my top recommendations for writers. I've left out Gone Home and Firewatch (two excellent games, but they are on every goddamn list), but I’ve included a wider range of games that pertain to the sections above, not just games with a fiction-like narrative. Some of these, like Rimworld and Kenshi, are difficult and best suited for people with at least some gaming experiences. Others, like Portal or The Walking Dead, are excellent for beginners.

- Portal (1 & 2)

- Soma

- Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice

- The Sims

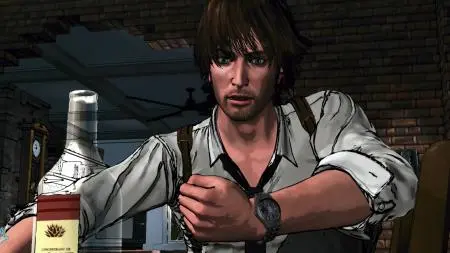

- The Walking Dead (Telltale, Season 1)

- INSIDE

- Rimworld

- Bastion

- The Fall

- Kentucky Route Zero

- Her Story

- Saints Row: The Third

- Kenshi

In Conclusion

It’s no secret that the best way to learn how to write is to write and read books, but another important factor in writing great fiction is taking inspiration from other mediums and synthesizing them into fiction. Video games offer a new perspective into the world of text, and can offer an immersive experience in new worlds — without the resultant expense or threat of loss of limbs.

About the author

Autumn Christian is the author of Ecstatic Inferno, We are Wormwood, and The Crooked God Machine.