No, we're not talking about this:

No, you don't need a motorcycle jacket to support your lower back for your Bizarre Bicycles:

And if you're looking to get a sculpted butt just like the ever-lovin', blue-eyed Thing, look elsewhere:

We're not talking about your thighs or your butt. You figure that stuff out on YOUR time. Nope, we're talking writing exercises from the experts in comics that just might save your prose.

Lynda Barry And How You're Journaling Wrong

You should be keeping a journal. You don't need me to tell you that. But what you might need is some advice on how to keep up with it. We all have that problem. You get a sweet notebook, maybe a new pen, and then this, FOR SURE, is going to be the journal you are REALLY going to use every day.

But it's hard. You forget. And then you get behind. And then you lose the little key that opens the lock on the front of your journal. Things pile up, and it's tough to keep journaling.

Lynda Barry's got a solution. And she knows what's up. Hell, she's been on the coloring Zen thing for years, instructing her students to color complex pictures with crayon as part of her classes.

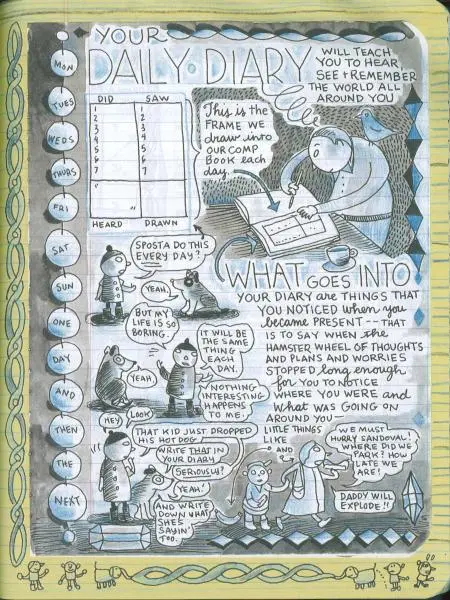

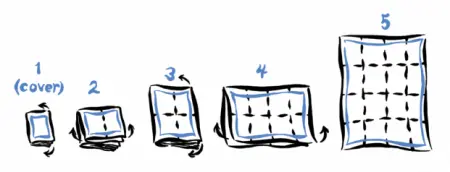

Check this out, Lynda Barry's journal page structure:

Instead of starting with a blank page, give yourself some boxes to fill. Take Barry's advice. Try it for a week. 4 minutes a day will not only leave you with a nice archive of phrases and actions, but will train you to be on the lookout for great material.

Ivan Brunetti's 5-Second Car

Ivan Brunetti has a great exercise for burrowing into the essence of an object.

Think of something complicated. Not complicated the way my feelings for Ke$ha's "Timber" are complicated. Something mechanically complicated. I'll use a chainsaw as an example. Probably because I just mentioned "Timber." Other good options include a bike, car, or one of those water jetpacks that are cool and still somehow underrated by society as a whole. It's a jetpack people. Sure, it only goes over water, but 70 percent of our planet's surface is water. Do the math.

For Brunetti's exercise, you'll draw the same complicated object a few times in a row. First, set a timer for 3 minutes. Draw your object, and don't let your pen stop the entire time. Keep adding detail until the clock runs out. Next, draw the same object, don't stop, but this time you've only got 1 minute. Then a third drawing, 30 seconds. Then 15 seconds. Then 5.

What you'll see is that your faster drawings focus on the essence of the object. If you chose to draw a chainsaw like me, you'll probably find your 5-second drawing breaks something complex down to a few basic shapes. A chainsaw comes down to its very essence.

You can do the same thing with your prose. Write a chainsaw. 3 minutes, no stopping. 1 minute. On down the ladder until you've got 5 seconds to create a chainsaw with words. Use visuals, talk about the weight of it.

What you're likely to find is a balance. Three minutes on a chainsaw is going to be too much. 5 seconds won't be enough.

What you're likely to find is the essence of an object. Which things have to be present in your description in order for something to be, truly, a chainsaw?

And what you're likely to find is you don't know a chainsaw as well as you think. Even if you've heard "Timber" enough times to wear out an MP3. Impossible, you say? I beg to differ.

Jessica Abel and Matt Madden's Foldy

For this exercise, we'll write an entire book. Get out a sheet of paper, 11x17 if you've got it handy. I don't know, maybe you've got extra sheets of paper in weird sizes. Maybe you're the one putting up the obnoxious, huge Garage Sale signs in my neighborhood. By the way, if that IS you, go ahead and feel free to look up the spelling of the word "garage." The answer might shock you.

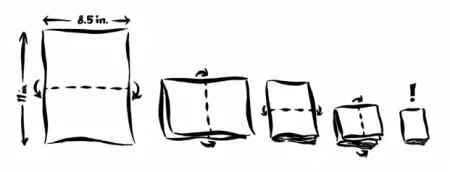

Take your paper and fold it according to the directions from our friends at foldycomics.com:

What you'll have is 5 sections. And you'll notice that each section is a little larger.

What we're going to do is write a story using each section as a discrete chapter or part of the story. Your first space, that's your intro. You don't have a lot of room to hook your reader, and you have to compel her to unfold to section 2. So make it good. Then, your next section, you've got a little more space. Use it wisely. Write something that earns the space. Give the reader enough they they want to flip to the next part. By the time you hit the last section, you should have enough going on to fill the space. Secondarily, you should try to not only use the space, but to also ramp up the excitement in each section. The largest section should contain not only the largest number of words, but also the most exciting content.

It's a great exercise where you, the writer, have to match the physical space limitation with an increase in action and excitement.

Jeffrey Brown's Tracing

Comics artist and writer Jeffrey Brown puts his classes through a simple exercise. Take a single, fairly complex panel from a comic, copy it as closely as possible, and then redraw it using your own style.

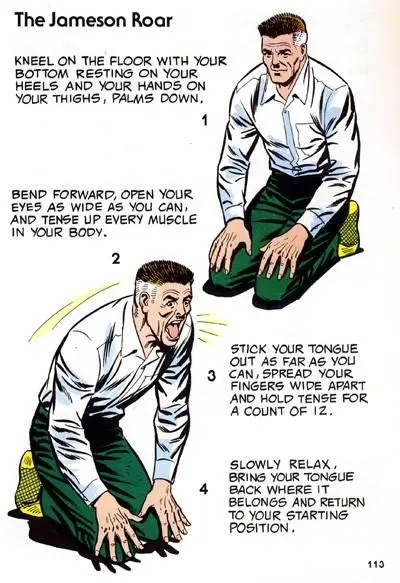

If you want to try it for yourself, might I suggest this gem?

When we talk drawing, it's very common for artists to learn by imitation, even tracing. Tracing is encouraged, good practice. They sell special paper for it, for the love of Odin.

In writing, we don't make tracing a habit. But we should.

Find a section of prose you really like. If you're not sure, try the last page of Jesus' Son by Denis Johnson. Copy it by hand. When you copy it by hand, you have to think about every word. You'll question why every word goes where it does, how it was all put together. When people talk about reading as a writer, this is a great way to access that skill.

There are worse things you could do than check out 10 books at the library and copy a page from each.

When you finish tracing, pick out a few of the things that make the section work. That make it tick. Then, write your own section using the same tricks.

Kochlalka and Crafty Enemies

James Kochalka got an avalanche of shit for his letter/essay "Craft Is The Enemy" in which he encouraged creators to stop perfecting their craft and start creating stuff. The strong reactions were understandable. Who wants to be told that 6 years and $100k of art school was a waste of time?

A cherry-picked, typical response:

The last thing modern comics is in need of are more naive artists lacking technical skills, when the majority of comics that are currently being published are already so horribly drawn that there’s little to be gained by looking at them

If I may, I think Kochalka's point wasn't that skill is worthless. His point was that waiting to create until all your skills are in place is a mistake. Keep working, and keep creating. You don't have to hone every skill before you start writing. You don't have to read the dictionary first. You don't have to read every classic.

Just get cracking. Read the dictionary on your breaks. Or do a couple Jameson roars. Either way.

About the author

Peter Derk lives, writes, and works in Colorado. Buy him a drink and he'll talk books all day. Buy him two and he'll be happy to tell you about the horrors of being responsible for a public restroom.