It's National Poetry Month in the U.S., which (of course) means it's time for an opinion-based list article. Today, I'm going to rank a variety of poetic forms. Some of these you're certainly familiar with while others may be new to you.

Because I am ranking these forms based on my personal experience and preferences, there's nothing "true" about this list. Hopefully, though, the examples and thoughts I share will introduce you to some new regions of the poetic landscape.

Side-note: In this article, I will be referencing poetry terms without defining each. Here, however, is a fancy-ass poetry glossary for you to use.

What I'm Not Including

There are many poetic forms missing from this list. There are three primary reasons for exclusions.

The first is that I don't view all poetry with rules or stipulations as necessarily belonging to a poetic form. This includes found poetry (which has rules focused on sourcing material), free verse (which is much more a not-a-form), and blank verse (which has such minimal rules that its net is cast excessively wide).

The second is that some poetic categories are defined more by subject-matter. I'm not covering those here, but it's worth acknowledging epic poetry, elegies, odes, list poems, pastorals, blazons, ekphrastics, and so on.

And the third reason is my limited insight into the wide world of poetry. Some forms I'm not including: the Chinese jintishi, the Welsh englyn, the Arabian ruba'i, the Korean sijo, the Urdu / Bengali ghazal, the minute, mirror poems, golden shovels—well, you get the idea. Poetry is vast.

Despite all these omissions, though, we have a substantial list to get through. Starting from my least favorite, here is my ranking of eleven major poetic forms.

11. Acrostics

I debated whether this even counted as a form, since it really has only one stipulation: You must spell something out (a name, a place, a phrase, whatever) using the first letter of each line. As such, there's lots of space for poets to play. It's tempting to think only of the grade-school variety, but there have been a great many with poetic merit.

I debated whether this even counted as a form, since it really has only one stipulation: You must spell something out (a name, a place, a phrase, whatever) using the first letter of each line. As such, there's lots of space for poets to play. It's tempting to think only of the grade-school variety, but there have been a great many with poetic merit.

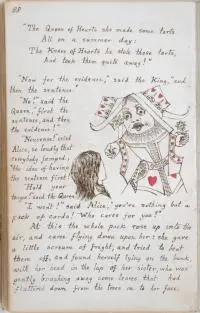

Take, for instance, Lewis Caroll's "A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky," which is an acrostic for Alice Pleasance Liddell (the same Alice for whom Wonderland was created). For its era, this is a perfectly enjoyable poem. However … is any of that because of the acrostic?

What acrostics offer are a bit of fun surprise when you realize that a separate message has made its way, in secret, into the poem. Such minor limitation means that acrostics can do all kinds of enjoyable nonsense, but very little of the good can actually be attributed to the form itself.

Final words: A form which adds an amusing twist—and almost nothing else—to a poetic work.

10. Limerick

The humorous and typically low-brow limerick is nothing to scoff at. They're catchy, they do a good job of setting up and delivering punchlines in a short space, and they're fairly accessible. Plus, residents of Nantucket and Leeds have gained great fame thanks to this form.

A virtue of note is the rhythmic variety. I'll avoid going too much into meter here, but the lines have a sing-song scansion that combines a variety of metrical feet, which lends both variety and momentum.

What causes this poor ranking is a combination of two things. First, it's such a strict, short, and simple form, with a rhyme pattern of A A B B A and a meter length that forces a sing-song style. But, more, there's little wiggle room when it comes to subject-matter or purpose. If you try to present a serious limerick, you'll be laughed out of the room. Likewise, attempting to write a funny but not-raunchy limerick may cause struggles. A Robert Gordon limerick said it well:

The limerick packs laughs anatomical

Into space that is quite economical.

But the good ones I’ve seen

So seldom are clean

And the clean ones so seldom are comical.

Final words: Fun, catchy, rhythmically intriguing, but ultimately too limited to be worth much exploration.

9. Villanelles

I admit more than the usual personal bias here. Villanelles, unlike many other low-ranking forms, are regularly taught in the classroom. As such, their vices have been magnified for me.

What is the largest of those vices? Simply put, there are far too many rules. You have prescribed rhythm, line length, stanza count, stanza length, and repetition of lines. All of these rules—and especially the degree of repetition—can easily burden the poem. I imagine many of these works could have done better if they shed the excessive formal confinement.

Are there good villanelles? Absolutely. The repetition can work well to emphasize certain themes or create a sense of spiraling around a thought. Famously, Dylan Thomas's "Do Not Go Gentle Into that Good Night" uses repetition to emphasize the need for a persistent fight for life. The most interesting villanelles, though, are ones that play fast and loose with the rules. My favorite is "One Art" by Elizabeth Bishop, which permits itself to add interjections and alterations to the repeated lines. In doing so, it builds to a wonderful poetic twist in the final stanza that makes great use of both the repetition and its subversion.

Final words: Despite some remarkable examples of the form done right, the intense restrictions and repetition make this an unwieldy form at best.

8. Sestinas

Sestinas are fairly well-known, though not so popular as sonnets or villanelles in the classroom. Their narrow prescription of stanza length makes them a bit awkward: You will always have six six-line stanzas followed by a three-line stanza. I've found it common that some portion of a sestina will seem like filler to meet that stanza quota.

The other primary rule is the repetition of end-words in a strict "rolling" pattern. However, since only the final word of each line has to be repeated, it leaves a lot of space to play with ideas and make the repeated words land effectively. To me, this is a good balance of leveraging repetition without over-using it.

There's something interesting about the way end-word repetition is used, and examples like Seamus Heaney's "Two Lorries" are worth checking out. Sadly, the merits end there for me. Frankly, I'm not a huge fan of sestinas—though they rarely irritate me in the way villanelles sometimes do.

Final words: This form has potential because of its minimal but still useful repetition, but the restrictive stanza structure and long-ish length make it tricky to do right.

7. Pantoums

Pantoums use repetition in a way that sort of "passes the torch." There's no rule for stanza length, but your second and fourth line of a given stanza will always become the first and third of the next. This then gets tied back together in a final stanza where line two and four are repetitions of the first stanza's line three and one. It creates a nice book-end effect.

Pantoums are one of my wife's favorites (actually, she had a lovely found-poem pantoum published a few years back). Here's the merit and downfall of the pantoum for me: While the pass-along method of repetition is intriguing, you have to be quite clever to avoid having the repetitions feel boring or inane. Of course, most modern pantoums play fast and loose with the rules, as they should. As a result, the repetitions are often skewed or altered somewhat, and that helps. I don't at all dislike the pantoum, but it's not a favorite.

Another interesting example to look at: "Parent's Pantoum" by Carolyn Kizer, which uses the repetition well and takes appropriate liberties with line alteration.

Final words: While I appreciate the unique take on repetition, the pantoum's requirement of two full-line repetitions per stanza can easily make poems feel dull.

6. Rondeaus

The repetition here is minimal: The opening phrase (or full line) repeats at the end of stanza two and three, creating a refrain. Traditionally (though less and less these days), each line should have between eight and ten syllables. The other rule is on rhyming, which really narrows the creative space of these poems. The rhyme scheme and length must be as follows: AABBA AABR AABBAR (with the Rs representing the refrain). Of course, when I say that the rhyming limits the creative space, I don't necessarily mean that as a bad thing.

I kept going back and forth between rondeaus and pantoums for this position. Ultimately, I placed rondeaus higher because so many of my students in Introduction to Literature resonate with the only rondeau I have them read: "We Wear the Mask" by Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Perhaps it's not the most brilliant of forms, but there's a lot to like. The rule-of-three refrain hits the sweet spot for me (useful but not overused) and the length feels satisfying for what the form offers. The rhyme scheme, for me, creates a forcefulness in the poem—and the rhyme exception helps emphasize the refrain.

Final words: While the rhyme-scheme and length can be limiting, this form hits the sweet-spot of repetition and does a lot to highlight the chosen phrase of your refrain.

5. Duplex

I have a soft spot for poetic forms invented in the modern era. Such is the case with the duplex, invented by Jericho Brown. The rules are fairly simple and have a similar "passing the torch" vibe to the pantoum: The poem is written in couplets with each first line repeating some (or all) of the prior couplet's second line.

I have a soft spot for poetic forms invented in the modern era. Such is the case with the duplex, invented by Jericho Brown. The rules are fairly simple and have a similar "passing the torch" vibe to the pantoum: The poem is written in couplets with each first line repeating some (or all) of the prior couplet's second line.

It's a lot of repetition, especially if you use the full line in the repeat. However, because the repeats are so close together, it feels more like a call-and-response to me. I feel this aspect shows especially well when a duplex is performed as spoken-word poetry.

My favorite duplex poem is "Duplex" by Jericho Brown (which gave the form its name), as I think it uses the right degree of alteration in its repeated lines.

Final words: While the repetition can sometimes feel excessive, the sense of call-and-response makes for an intriguing (and novel) form of poetry.

4. Sonnet

I love sonnets. Maybe I shouldn't: They have the restrictive rhyme scheme, stanza length, and rhythmic requirements—elements for which I've penalized other forms. But, damn. I just love a well-written sonnet.

There are three things I like about them. The first is that I find their restrictions fairly well-balanced, whether we're talking about the Shakespearean or Petrarchan variety. You have exactly fourteen lines, but that's not over-long or over-short. You have mandatory rhymes, but no single rhyme is forced in excess.

The second is that its form does a great job of emphasizing the "turn": In a Shakespearean sonnet, the "turn" typically happens in the final couplet, with a new take or twist on the idea found in the first portion of the poem. It forces you to re-contextualize what came before. You're probably familiar with Shakespeare's own "My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun," which seems to be criticizing his mistress until the final lines take it in a new direction.

The third is that the forced iambic pentameter does not have to be, in fact, iambic pentameter. John Donne is my favorite in this regard. He was so off iambic pentameter that Ben Jonson once said "Donne, for not keeping of accent, deserved hanging." But that's just the thing: Because you know to expect the iambic pentameter, the actual rhythm of a given sonnet plays with the iambic as a sort of background music. To me, it's like jazz. My very favorite in this regard is Donne's "Batter my heart, three-person'd God." So sexy. So, so sexy.

Final words: With well-balanced restrictions, rhythmic play, and a well-emphasized poetic turn, the sonnet is among my favorites.

3. Haiku

In the original Japanese, the form has a prescribed syllable length per line: 5 / 7 / 5. Personally, I find haiku work better in translation if they drop this requirement and instead convey the sentiment and imagery.

Of course, the 5 / 7 / 5 structure is an important formal requirement if you're writing your own. However, despite being the main thing people think of, it's not the only thing that makes a haiku a haiku. Traditionally, these bite-sized poems are meant to capture a moment in time, often focusing on a singular image. This makes haiku trend toward being concrete and sensory. Additionally, the intensely short length means that—of necessity—a good haiku has carefully considered each and every word. At its finest, a haiku can also include—in that short space—a dash of surprise.

So, yes, clearly I love haiku. Rather than continuing to ramble about them, though, let me just drop three of my favorite haiku by my main man Issa:

What good luck!

Bitten by

this year's mosquitos too.

Writing shit about new snow

for the rich

is not art.

Last time, I think,

I'll brush the flies

from my father's face.

Final words: Haiku combine attention to imagery, careful word choice, and a dash of surprise to capture a moment in time.

2. Tanka

The tanka is like the big brother of the haiku. Its structure is the syllabic 5 / 7 / 5 / 7 / 7. In almost all of its merits, it's the same as the haiku: It focuses on imagery, it captures a moment in time, it mandates careful word choice, etc., etc. So why does it place higher?

The tanka is like the big brother of the haiku. Its structure is the syllabic 5 / 7 / 5 / 7 / 7. In almost all of its merits, it's the same as the haiku: It focuses on imagery, it captures a moment in time, it mandates careful word choice, etc., etc. So why does it place higher?

For me, the tanka combines one of my favorite elements of the sonnet with all of my favorite elements of haiku: A tanka is like a haiku with a poetic turn or twist in the final two lines. Sometimes that's a new image but more often it's a reinterpretation of the image established in the opening.

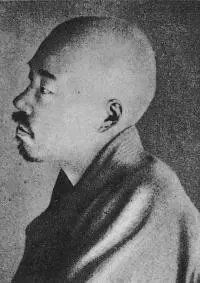

Here's a translated tanka from Shiki:

The bucket's water

poured out and gone,

drop by drop

dew drips like pearls

from the autumn flowers.

Here's one of mine, which I recall spending an excessive number of hours tweaking:

Frosted bark shimmers

on barren trees ablaze with

fading amber light,

their hissing breeze pleading to

never be silhouetted.

Looking at that tanka of mine now, I'm not entirely sure I like it (especially the last lines). However, it was still a massively informative exercise in paying attention to words, sounds, and images.

Final words: While carrying all the merits of the haiku, the tanka also adds an emphasis on the feeling of surprise with a dedicated turning point.

1. Cleave Poem

I was introduced to the cleave poem thanks to a reading done by Jamaal May, though I believe that the form is a modern invention from Phuoc-Tan Diep. Here are the rules: You are writing three poems in one by splitting each line in two parts. The first column, second column, and combined column readings should all make sense and stand on their own.

I find it hard to explain the exact appeal; frankly, I just find the results of this form super cool. It requires you to pay attention to line breaks and the meaning of each piece as it stands on its own. It needs to be strung together in a way that illuminates how language can connect differently to shape new meaning. I haven't read a huge deal of cleave poetry, but almost all of it has been fascinating. Here are a couple examples, which I believe speak for themselves:

Miracle on the Hudson

by Dave Schneider

A flock of geese flying on course

in formation and a jet airliner

tending to business in the winter sky

met destiny when danger converged

in one fateful moment without warning.

Plucked from the sky without power

there were no second chances

survivors were brought to loved ones

in this drama by a skillful crew.

November

by Phuoc-Tan Diep

The sun weeps cider tinted tears

for Summer for the fading

for the moon that hides light

behind the trees as Autumn leads Winter

shivering and anaemic by the hand

By the by, if anyone can find Jamaal May's cleave poem, send it to me! It's what made me fall in love with the form, but I have struggled to find it anywhere.

Final words: This modern invention plays with language in a way I've rarely seen elsewhere. Its focus on line breaks and the flow of language make for tricky but fascinating poems.

And there you have it: My ranking of eleven poetic forms. But what about you? What favorites did I fail to cover or place incorrectly on my list? I'd love to hear your perspective.

Get The Teachers & Writers Handbook of Poetic Forms at Bookshop or Amazon

Get The Making of A Poem at Bookshop or Amazon

About the author

Rob is a writer and educator. He is intensely ADD, obsessive about his passions, and enjoys a good gin and tonic. Check out his website for multiple web fiction projects, author interviews, and various resources for writers.