Header image via Wikipedia Commons

While a "Webster's" was a regular feature of my bookshelf growing up, I never thought anything about the man, himself, until recently. When I did some research, I learned that he was a manic intellectual and a bit of an anti-social blowhard. He was well known in his time for being overly confident and fussy, mouthy and self-serving, but also a bit of a loner and a weirdo.

These habits and obsessions were what led him to undertake a lifetime’s worth of achievements that we still benefit from today. In addition to giving us a massive book of words, he also revolutionized education, spelling, grammar, and lexicography. He was almost entirely responsible for laying the foundations of the American-style English we use today. While there are MANY interesting things about the man and the changes he pioneered for the English language, here a few that I thought were especially interesting.

1. A Founding Father?

Webster was a little younger than most of the people who would go on to create the United States government. In fact, to call him a "Founding Father” might be a bit of a stretch; he was more like your cool Founding Uncle—the youngest brother of The Founding Fathers.

Noah Webster, Jr. (10/16/1758 – 5/28/1843) was the second to last child of Noah Webster Sr. and Mercy Steele Webster. Both his parents came from families that had lived in the American colonies since the early 1600s—Webster’s great-great grandfather, Lieut. Robert Webster was born in England in 1619 and moved with his parents to what would become Hartford, Connecticut. Mercy Steele’s first American ancestor, John Steele, travelled from England to Massachusetts Bay in 1633. So, with almost 140 years of family living in the New England area, it’s pretty obvious to see that Noah Webster’s affiliations were on this side of the Atlantic.

Noah Webster entered adulthood during a pivotal moment in the history of the young country. He was just 16 and a freshman at Yale when the Battles of Lexington and Concord marked the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Webster, like many of his peers, was heavily influenced by the prevailing attitudes of patriotism and American DIY-ism that characterized the time and the people in his community. Webster enlisted and served, but he spent much of the war years teaching and writing the book that would make his name. His influence was not so much on the formation of the country itself, but on how the new country would educate its young and communicate with each other.

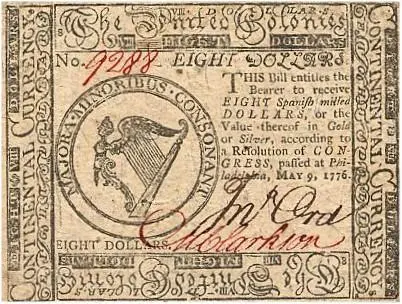

2. Got Started with an Eight-Dollar Bill

After Noah graduated from Yale, his father gave Noah an $8 dollar bill and told him he was on his own. The bill, some leftover Continental Currency, was barely worth $4. Noah’s family had pedigree, but not wealth. His father had to mortgage his farm to send Noah to college, but it was in the middle of the war, so by the time he graduated, the Websters, like many people at the time, were strapped for cash.

At first he taught school. Then quit. Studied law. Then quit. Was depressed for a year. Studied law again. Passed the bar in 1781…but he couldn’t find work as a lawyer. Then started a school. It was very successful! But, he quit that (see item 10…) and moved and started another school. Then he had his million dollar idea! By 1785, he had written the 3 books that would make him a household name and would keep money in his pocket for the rest of his life.

3. Introduced Age-Appropriate Learning

When Little Noah entered school at the age of 6, he attended one of five primary schools in his region. Connecticut and Massachusetts required children to attend school, but the schools themselves were awful. A typical schoolhouse in the 1760s was one room, cold, and crowded. Kids of all ages, sometimes up to 70 at a time packed the small school houses. There were benches—no desks, few books—mostly outdated texts from England, and a stereotypically stern schoolmaster who ruled the classroom with a combination of idleness and violence. (Webster later called the teachers of that era the “dregs” of society.)

When Webster was himself a teacher, he was inspired to write his first books on learning. Three volumes, collectively called A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, consisted of a spelling book (published in 1783), a grammar book (published in 1784), and a reader (published in 1785). The spelling book allowed the student to progress by age. The lessons moved from learning just the letters in the alphabet, to sounds the letters make, to simple words, to more complex words, and then to sentences. This teaching method was revolutionary, and his books sold millions of copies, changing forever how education was structured for millions of children in the United States. It was an instant success and the proceeds sustained Webster for the rest of his life…AND made it possible for him to afford a 28-year effort to write the dictionary that we all recognize. It was the most popular spelling book for over a hundred years, selling over 60 million copies by 1890 (some 40+ years after Webster’s death).

4. Pro-English, Anti-British

In the earliest years of American independence, Webster lobbied for an Americanized English that was different from British English, but that also unified the territories of the new United States. He argued that if everyone in the new country spoke and wrote the same language, “the consequence of this uniformity will be an intimacy of social intercourse hitherto unknown, and a boundless diffusion of knowledge.”

In order to distinguish American English from British English, he promoted simplified spelling (more on that in number 8) and he argued that the simplified spellings were more in line with English’s Anglo-Saxon etymological origins. In England, the dominant culture wanted to align itself with the Classical era of the Greek philosophers and Roman emperors, so lexicographers of that time forced Anglo-Saxon words and grammatical structures into Greek and Latin frames. In his book Noah Webster and the American Dictionary David Micklethwait tells us:

Webster had discovered that some of the usage condemned by grammarians as bad English was actually good Anglo-Saxon. He also found instances of accepted usage which he felt compelled to condemn because it was not good Anglo-Saxon. One such word was island:

The Saxons wrote the words igland, ealond, and ieland, which, with a strong guttural aspirate, are not very different in sound. It is a compound of ea water, still preserved in the French eau, and land—ealand, water land, land in water, a very significant word. The etymology however was lost, and the word corrupted by the French into island, which the English servilely adopted, with the consonants, which no more belongs to the word, than any other letter in the alphabet. Our pronunciation preserves the Saxon ieland, with a trifling difference of sound: and it was formerly written by good authors, iland.

5. A Loner, Dottie, But Not Much of a Rebel

It’s probably not much of a stretch of your imagination to see little Noah sitting under a tree, reading books instead of performing his farm chores. An awkward kid, he liked books and music more than physical pursuits. As he grew, he became known as a fastidious person, not particularly jocular. He immersed himself in his books and was minimally social—though he did have friends.

That’s not to say he was shy, though. Imbued with a certainty that he must do something great for society, the bombast to believe he has the answers, and a near manic work ethic, he seemed to approach any task with dogged determination and meticulous attention to detail.

As an adult, he was known as a bit of a blowhard and oddball. He counted houses and churches when he travelled through towns, recording his findings in his diary. While travelling across the American territories in 1785 and 1786, he tallied 20,380 houses in 22 cities. He also shared that information with other people who counted houses, a sort of Colonial Nerd Network. He kept records of practically everything he did and made copious notes in the margins of anything he read. He assumed every word he wrote would be interesting to someone in the future. He kept copies of letters he wrote to public figures and even kept their replies. He even re-packaged and published his own writings from when he was young—basically the equivalent of republishing your college thesis and your high school history essays for posterity. By the time he was in his 70s, he had volumes of notes, letters, essays, and diaries that he stored and saved. He even WILLED this collection to his son-in-law. His hubris (and foresight) did, however, give us a very detailed look into his life and work.

6. Hanging with Hamilton & Friends

So, while he was just a kid when the Revolutionary War started, he did manage to rub elbows with some of the Founding Fathers. He gained notoriety writing and publishing pro-Federalist essays, so when Alexander Hamilton wanted to start a daily paper in New York City in 1793 he loaned Webster $1500 (which is roughly $38,000 in today’s money, if an online inflation calculator can be believed!) to move to NY and start the paper. Webster ran and edited the paper for 4 years and cemented his identity as a Federalist spokesperson.

He had run-ins with other big names of the era. The “Blue-Backed Speller” was so popular that even Benjamin Franklin said he used it to teach spelling to his grandchildren. The fame he netted from it also earned him a dinner in Mt. Vernon with the retired first president, Old G.W. himself. At the dinner, Washington mentioned that he was hiring a Scottish tutor for his grandkids. Webster told him to hire an American as a tutor instead. Instead of tossing the young blowhard out the door, Washington offered the job to Webster, who declined.

7. Recorded 70,000 Words, But Coined Only ONE

Though Webster made his name with the spelling book, he cemented his posthumous legacy with his dictionary. The first dictionary Webster published was called A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language and he released in in 1803. In 1828, he published his masterpiece An American Dictionary of the English Language. It didn’t sell so well at first. A second edition published in 1841 sold better, but it wasn’t until after Webster died in 1843 that the dictionary sales took off. In 1845, George and Charles Merriman acquired the rights from Webster’s heirs and printed the first copy with the Merriman name.

The dictionary itself was a huge accomplishment. It had over 70,000 words, and many of them had never appeared in a dictionary before. He learned 26 languages, including Old English, French, Spanish, Hebrew, Greek, Arabic, Latin, Italian, German, and even Sanskrit. Some people at the time criticized him for having too many vulgar words—like piss and buggery. He reacted by noting that he had actually removed most of the vulgar words from a commonly used dictionary at the time such as arse, bum, fart, and turd.

In addition to a nice selection of swear words, the dictionary included words used only-in-America like squash, chowder, hickory, skunk and applesauce. Some sources credit him with adding words he invented like afterwise, which sort of means 20/20 hindsight, and zuffalo, a small flute, primarily for communicating with birds. Webster, himself, only claims to have invented one word: demoralize.

According to Micklethwait, the word first appeared in a pamphlet from 1794 called The Revolution in France, considered in Respect to its Progress and Effects. By an American. The word appeared in this sentence:

All wars have, if I may use a new but emphatic word, a demoralizing tendency.

He meant the word to mean lessening the moral value of something, not the more modern usage that means to discourage or dishearten. While it IS the first recording of the word in print in English, it’s fairly likely that Webster, who was translating French newspaper articles at the time, adapted the French word demoraliser into an English version.

NOTE: If you want a list of some of the other “new” words he added to the dictionary, check out this short glossary from Merriam-Webster.com.

8. He Simplified the Spelling of Many of Our Words

Webster preferred a more phonetic spelling for English words. You may think that modern American English is full odd phonetics and inconsistent spellings, but before Webster’s reforms, it was much worse. He believed that some common spellings were unnecessarily complex and confusing. Instead, he advocated that the u be left out of words like colour and honour. He suggested that the extra k in publick and musick was unnecessary. He reversed the re endings to er in words like theatre and centre.

Some of his reforms stuck, though some did not. Here is an excerpt from his 1789 work An Essay on the Necessity, Advantages, and Practicality of Reforming the Mode of Spelling and of Rendering the Orthography of Words.

A substitution of a character that has a certain definite sound, for one that is more vague and indeterminate. Thus by putting ee instead of ea or ie, the words mean, near, speak grieve, zeal, would become meen, neer, speek, greev, zeel. This alteration could not occasion a moments trouble; at the same time it would prevent a doubt respecting the pronunciation; whereas the ea and ie having different sounds, may give a learner much difficulty. Thus greef should be substituted for grief; kee for key; beleev for believe; laf for laugh; dawter for daughter; plow for plough; tuf for tough; proov for prove; blud for blood; and draft for draught. In this manner ch in Greek derivatives, should be changed into k; for the English ch has a soft sound, as in cherish; but k always a hard sound. Therefore character, chorus, cholic, architecture, should be written karacter, korus, kolic, arkitecture; and were they thus written, no person could mistake their true pronunciation.

His earliest editions of the dictionary advocated a drastically different spelling system that was very phonetic. Each successive edition was a bit more conservative and he received pushback for the more extreme re-spellings. But, still, his innovations in education and spelling were incredibly influential in making American English more consistent and somewhat more sensical.

9. Nationalized Copyright Laws in the Young U.S.

Noah Webster gets a lot of credit for this—much of it, he gives himself, but David Micklethwait spends nearly an entire chapter of his book explaining that most of Noah’s effort to secure a copyright law were either in vain OR for his PERSONAL betterment and not for the nation as a whole. During the 1780s, Webster travelled to petition that his work be protected. At the time, many new states were considering passing laws that mirrored a 1710 British law called The Statute of Anne that allowed a copyright to last 14 years, instead of 2. (The Statute of Anne never actually applied to the American colonies. They were considered agrarian in nature, and the British government obviously didn’t think that much real worthy literature was likely to arise there.) Whether or not a state passed such a law doesn’t seem to have anything to do with whether or not they were visited by Noah Webster, though there is one instance in January of 1783, in New York. Webster arrived to request exclusive right to print, publish, and sell his spelling and grammar books, but he was intercepted by Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law. Here is Webster’s account:

The necessity of such a petition was prevented, by the prompt attention of General Schuyler to my request, through whose influence a bill was introduced into the senate, which, at the next session, became a law.

A federal law was finally passed in 1790—the US Copyright Act of 1790, but whether or not it was the result of Webster’s constant lobbying is a matter for debate.

10.None of This Might Have Happened If He Didn’t Get Rejected—TWICE.

After college, Noah tried to make his living by setting up a private school in Sharon, Connecticut. The school was successful and well-attended by the children of well-off patriots who had fled New York City after it fell to the British in October of 1776. While in Sharon, he spent time in the household of the wealthy Smith family. Juliana Smith was 20 years old and edited the magazine of the Sharon Literary Club, of which Noah was an enthusiastic member. At club meetings, members shared their writings with each other and debated.

On one occasion, Noah shared an essay and Juliana was not impressed. In a letter to her younger brother, she said Webster’s “reflections are as prosy as those of our horse.” Of Webster, she noted that “in conversation, he is even duller than in writing, if that be possible.” While it seems pretty clear that the smart, literary-minded Juliana would have totally been Noah’s type, she wasn’t interested. He did, however, seem to hold a candle for her, as he named his second child Frances Juliana.

It's also said that he courted Rebecca Pardee, but she had a relationship with a soldier who’d gone to war. When he came back, her pastor encouraged her to stay with the soldier and break it off with Noah Webster.

Though Webster never says so himself, shortly after the second rejection, he closed the school suddenly in the fall of 1781 and left town. After sulking through the winter months, he moved to Goshen, New York and opened a new school. At the time, he described himself (in 3rd person, because that’s the kind of navel-gazer he was…) like this:

...his health was impaired by close application, & a sedentary life. He was without money & without friends to afford him any particular aid. In this situation of things, his spirits failed, & for some months, he suffered extreme depression & gloomy forebodings.

Despite his dreary musings, it wasn’t like Noah to let disappointment slow him down too much. Not long after moving to Goshen, he began writing the three books that would elevate him from Regular Schoolmaster to Revolutionary of Education and Inventor of American English.

If you want to learn more about this interesting character, check out these websites and books:

Get The Forgotten Founding Fathers at Amazon

Get Noah Webster and the American Dictionary at Amazon

Get Noah Webster: Man of Many Words at Amazon

About the author

Taylor Houston is a genuine Word Nerd living in Portland, OR where she works as a technical writer for an engineering firm and volunteers on the planning committee for Wordstock, a local organization dedicated to writing education.

She holds a degree in Creative Writing and Spanish from Hamilton College in Clinton, NY. In the English graduate program at Penn State, she taught college composition courses and hosted a poetry club for a group of high school writers.

While living in Seattle, Taylor started and taught a free writing class called Writer’s Cramp (see the website). She has also taught middle school Language Arts & Spanish, tutored college students, and mentored at several Seattle writing establishments such as Richard Hugo House. She’s presented on panels at Associated Writing Programs Conference and the Pennsylvania College English Conference and led writing groups in New York, Pennsylvania, and Colorado for writers of all ages & abilities. She loves to read, write, teach & debate the Oxford Comma with anyone who will stand still long enough.