…99 out of 100 screenplays I read [aren't] good enough… When you read a good screenplay, you know it – it’s evident from page one. The style, the way the words are laid out on the page, the way the story is set up, the grasp of dramatic situation, the introduction of the main character, the basic premise or the problem of the screenplay – it’s all set up in the first few pages of the script. — Syd Field Screenplay (1979)

Good screenplays are like sonnets. They’re elegant, simple, rhythmic, adhere to a specific structure, and nail a problem/solution within the requisite number of lines. They’re a joy to read. Unfortunately, as Field lamented in 1979, they’re extremely rare.

Despite the hundreds of seminars, books and DVDs Field (along with McKee, Knopf, Voegler, Seger, Truby, Snyder et al) has contributed to teaching the science of screenwriting over the past four decades, it’s still a form that very few people manage to write right. And the numbers are getting worse. In 1979, a screenplay was an analogue manuscript, bashed out a page at a time on a typewriter. A mistake, or a rewrite, involved weeks of retyping. Once completed, the final product had to be copied at great cost, bound with covers and brads, and mailed (with the correct postage) to each prospective reader. When Field said 99/100 screenplays weren’t good enough, he was talking about 100 of these precious, handcrafted documents, these labors of love.

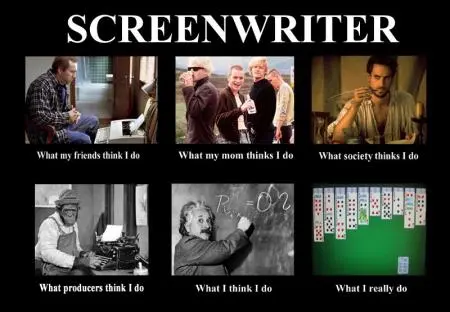

Now, any idiot with script software can vomit their twelve-stepped thoughts into a laptop, convert to a pdf, hit send and voilà! Instant screenwriter. Tens of thousands of them. Monkeys with typewriters on crack. Thanks to technology, there are more unproduced screenplays out there in cyberspace than there are photos of Kim Kardashian. And most of them, 99.9% of them, are bad, occupying all points on the bell curve between eye-gougingly horrible and utterly mediocre.

I know this because I read, on average, somewhere between 400-500 screenplays a year. I read competition entries by complete unknowns and scripts about to go into production written by (and starring) A-listers – and everything in between. There’s no guarantee of quality at any level. Some scripts are so badly written that after a few pages I start to think I’ve had a stroke, and my brain no longer has the capacity to process language. Many are competently done, but they’re dull, full of cardboard stereotypes and stock situations, predictable and small-minded. A tiny, tiny minority sing on the page, enthrall me while I’m reading, stay with me for weeks afterwards, and ensure that I’m first in line to see the movie when it finally gets screened.

It’s difficult to say exactly what defines the good ones. Unfortunately, despite what the gurus say, screenwriting is an esoteric art, not an exact science. There’s no 'one size fits all' formula for writing a kick-ass script. The magic comes when the writer knows the rules and bends them, acknowledges expectations then challenges them. As William Goldman famously said about the scriptwriting process, “nobody knows anything.” If you’re an established screenwriter with an ongoing deal, you can ignore all advice. You can dump that 160-page, multi-protagonist, spiraling free verse epic on your producer’s desk and still get paid. However, if you’re still at the stage of honing your spec script, hoping it’s going to be picked out of the tsunami of sludge and actually read by someone who’ll recognize your talent, you need to be aware of the all-too-common shortcomings that will get your beloved creation tossed in the “HATE! SMASH!” pile.

A lot of these involve simple courtesy towards your reader (Proof-read! Format correctly!). If you’re lucky enough to get an industry reader’s attention, you need to make sure you’re telling the best, the cleanest, the most polished story within your capabilities. It needs to conform to parameters and be a fast, enjoyable read. Don’t make your reader work too hard to get to the juicy bits. Save the non-linear multi-voice historical epic for after you’ve won your Academy Award. Or write a novel.

My bottom line for assessing whether a screenplay is any good or not is simple: Is it a page-turner? Am I captivated from FADE IN till FADE OUT? Do I notice anything except the story until the story is done? Here are ten frequent faults that disrupt my read. They jolt me out of the carefully constructed narrative world and dump me back into reality, wondering if the cat litter needs changing or whether I could use another coffee. When that happens, it’s over, and I'm on to the next. There's a never-ending pile to pick from.

1. No One Else Has Read It

It’s all too obvious when I’m entering virgin territory as a reader. If mine are the first eyeballs (other than the writer’s) to scan the pages, invariably they’re peppered with typos, incorrect usage of apostrophes, wrongly used words, random character names, formatting errors, confusing sentence structure, and all manner of monstrosities that disrupt my engagement with the text and have me wanting to claw my own cheeks off. If you have a poor grasp of the technicalities of English language usage, no one wants to read your work. Good grammar and correct formatting are basic entry level requirements. Clarity and accuracy of language use = clearly communicated thought. If you don’t get this right, nothing else matters.

FIX: Proof read, don’t just spell check. Have someone else go through your script line by line with a red pen if necessary. Three times. Ask them to appraise your logic and continuity in addition to highlighting language mistakes. Watch out for spelling errors in scene headings. Check you know the difference between homonyms (peak/pique/peek and discreet/discrete seem to be particular offenders). If you’re floundering, take Taylor’s class. If English isn't your first language, work with a native speaker. Both screen directions and dialogue are driven by idiom.

2. You Wrote What You Know

Too many writers make the mistake of thinking their life is a movie. Mostly, it’s not. The sludge pile contains hundreds of navel-gazing screenplays about 20-something wannabe writers doing bong hits and angsting about the girl that got away while their idiotic best friend messes up a drug deal and conflicts with the local thugstabulary. There are also a lot of screenplays out there about personal fights to overcome addiction or child abuse. Or biopics about Grandpa the war hero. Or assistants retaliating against their bosses. Your reality may be painful and melodramatic. You may have done an amazing thing by recovering from disease or hardship. But the hard truth is that your life may not be of the slightest interest to a mainstream audience. The big screen is notoriously unforgiving of small stories, especially the generic struggles that make up everyday existence.

FIX: Get some perspective. Quit your comfort zone. Put ten years and thousands of miles between yourself and the life events you want to write about. Experience as many situations and meet as many people as possible in order to develop your writerly instincts. Distinguish between happenstance and instances of broad emotional truth. Read, watch, learn. If you still think your life is a movie, consider that the best stories are often told by outside observers - switch perspective.

3. You Wrote What You Didn’t Know

Isn’t the Internet brilliant? Without leaving your desk you can look up street maps of any city in the world, check fashions from any period in history, the symptoms of any mental illness or the legal penalties for drunk driving in any state in the nation. Furthermore, you can tap into the life experiences of thousands of different individuals via their blogs and Twitter feeds and develop an authentic voice for your characters. Research has never been easier – or more necessary. The down side is that your trail can be followed. Most script readers read electronically, which means entering a questionable fact into Google for verification is a moment’s work. You’d better hope your research holds up because nothing smashes suspension of disbelief faster than a glaring factual error.

FIX: Become an insider. Whether your characters are rodeo clowns or investment bankers, you need to use their jargon, understand their risks and opportunities, map their environment. Read books to gain an in-depth understanding rather than relying on internet chatter. But remember that the best research NEVER manifests directly on the page in the form of awkward exposition. It manifests as relaxed, confident authenticity. Make your characters’ world your own, not the other way round.

4. You Don’t Have A Clear Protagonist

Too many screenplays drift along for pages and pages before it becomes apparent who the story is about. Lots of characters are introduced as though they are of equal importance and the narrative jumps from person to person. Then, once the protagonist emerges, it takes her ages to make a decision, or do anything but react to circumstances. Minor characters steal scenes from her. She doesn’t have a plan. She doesn’t want anything. She lacks direction. So I stop caring what happens to her and start investigating my lunch options.

FIX: When I enter your narrative world, I’m completely lost. I don’t know where I’m going, or what’s important. I need a guide. This isn’t a novel, where I can cope with an omniscient narrator and jumping in and out of different characters’ heads. I need an individual to be driving this story from as close to p.1 as is possible, making all the important decisions and defining direction. Because this story will eventually be organized through the single eye of a camera, I need to know whose perspective the scenes are coming from. I need to know whose side I’m going to pick in a fight. And I need to know it quickly. If I’m still asking “Whose story is this?” by p.10, I’ve failed to engage. I also need to identify your protagonist’s goals very early on, because this dictates the structure of your narrative. Your story is done when she gets what she wants. As a bonus, give me a protagonist who is so unique and fascinating that I form an emotional bond with her during the course of the script and will cry when we finally reach her HEA.

5. You Failed To Pick A Genre

I like reading Westerns. I know as soon as I see the first scene heading with a date in the 1870s and a location named after a Gulch that there will be cowboys, whores and big sky, and I dial up my expectations accordingly. Anything that starts with a mass slaughter in a sorority house also gets a thumbs-up because I know I’m reading a horror film from the top. Too many screenplays lack this definite identity and start out as a bland, could-be-anything introduction to some generic characters waking up and making breakfast. The tone is inconsistent, with crass sexual innuendos in one scene and a car wreck in the next. Because I don’t know the writer, or their intentions, I don’t know if what I’m reading is meant to be funny, or scary, or ironic. I don’t know if it’s succeeding or failing. It fails to induce any response in me. I forget what I’ve just read and have zero anticipation for what might come next.

FIX: Grab your reader by signaling exactly what your story is in the first five pages. Use a prologue if necessary to demonstrate that you have a clear grasp of genre conventions – you can challenge expectations later. If you’re writing a thriller, start with a crime, if it’s a romcom, send your protagonist on a date. If you’re writing a comedy, the tone of your humor should be consistent from page one. If you’re not sure what genre you’re writing in (or can’t identify it as anything other than ‘drama’), you may not be working with material that’s distinctive enough for a spec script.

6. There Are No Rough Edges

Sometimes screenplays are too smooth to be true. Everything’s by the (usually Save The Cat) book, with each plot point precisely placed and the hero twelve-stepping her journey like a seasoned pro, transforming completely in the process. Every first half set-up is neatly paid off in Act Three. Every minor character’s curve ends in resolution. The bad guys end up in handcuffs and the hot male and female lead sail off into the sunset for some mind-blowing sex. Everyone has perfect teeth, impeccably highlighted hair, and lives inside a Crate & Barrel catalog. It’s exactly the same as the last identikit script: dull, predictable, plastic, forgettable. I learn nothing new from reading it. It takes me nowhere I haven't been before.

FIX: As humans, we are defined by our flaws, driven by our imperfections. We learn lessons from failure, not success. We’re constantly aware that life is long and happiness is fleeting. When someone tells a story that seems too good to be true, we don’t buy it. The narratives and characters that have rough edges and dangling threads seem more real and believable. They have depth. We engage with them because they force us to ask questions rather than delivering all the answers. Does everyone in your screenplay get what they want or deserve by the end of Act Three? Mix it up.

7. There’s Too Much On The Page

The last thing a screenplay reader wants to be confronted with is a dense block of text. Too many words. I like white space, the quality known as ‘verticality’ that enables the eye to sweep swiftly down the page with all the vital information jumping out. I’m only interested in plot and characterization as revealed through action and dialogue. Everything else is irrelevant. It’s not the screenwriter’s job to be a set or costume designer, or director of photography, or music editor. It’s especially not the screenwriter’s job to direct actors from the page, via the use of parentheticals, gestures or dictated line readings (underlining for emphasis, including pauses, writing accents phonetically etc). Adding irrelevant details makes you look like an amateur, or even an obsessive control freak. It also inflates your page count.

FIX: Streamline. Trim. Downsize. Remove every single word that isn’t absolutely necessary to telling your story. There should be no camera or music cues or lists of emotional responses currently being experienced by a character. Eradicate adverbs and adjectives. Paragraphs of screen directions shouldn’t run more than three lines. And, ultimately, you should slim your script down so it hits a sweet spot of between 93-103 pages in length. The tauter the better. If you’re an unknown writer, asking a reader to wade through much more than this is presumptive, quite possibly even rude, depending on the quality of your writing.

8. There’s Not Enough On The Page

Sometimes screenplays are too simple. There’s nothing there. Superficial characters walk through an episodic series of situations and end up exactly the same as they started. Dialogue is always on-the-nose. No one gets hurt. There are no ongoing, unresolved issues. No thematic links. No dramatic irony. No subtext. No suspense. No sub-plot. No substantial supporting characters threatening to derail the whole narrative. No obstacles between the protagonist and her goals that last more than a scene or two. It’s a “this then that” narrative. This happens, then that. For 90-odd pages. The end. This is a particular problem with romcoms.

FIX: The best screenplays are only simple on the surface. There are all kinds of sophisticated narrative techniques crunching away beneath the single words of dialogue and meaningful stares. Learn about subtext and how perceived meaning drives a scene rather than the lines characters speak out loud. Read Jon Gingerich’s excellent piece on Understanding The Objective Correlative and use symbols to inform the story. Learn how to create suspense using Barthes’ action and enigma codes. Upgrade your writerly toolbox.

9. It Fails The Bechdel Test

Women buy more than half of all movie tickets. Women, in all their diversity of color, sexuality, class and creed, enjoy seeing themselves represented on screen. You might be surprised, therefore, how many screenplays fail this simple test:

(1) Does it have at least two women in it, who

(2) talk to each other, about

(3) something besides a man?

I read too many screenplays where the ONLY female character is the protagonist’s girlfriend. She’s described as “blonde, 25”. She has no function within the story other than as penis-wrangler. Every other character, every cop, clerk, carpenter and CEO encountered is male. Other screenplays deign to include additional female characters, but only if they’re (as Shirley Maclaine once lamented) victims, doormats or hookers. Stereotypes abound, such as the Plucky Single Mom Waitress or Whiny Wife. Do these writers not know any real women? Why do they keep recycling the ones they’ve seen in other movies? The more times you see these tired old tropes trotted across the page the more teeth-grinding it gets.

FIX: Stereotypes – whether of gender, color, sexuality, age or ethnicity – are bad. They’re used by lazy writers with no insights to offer about the human sprawl. Diversity is good. If your story contains an array of characters with different voices, it’s more likely to seem fresh and exciting – and demonstrate your skill as a writer in making those voices authentic. Also, you never know who’s reading your screenplay. If you steer clear of stereotypes, you’re less likely to offend.

10. It Lacks The Z-Factor

You have no idea how excruciatingly painful screenplays can be until you’ve read a few thousand. Sometimes, nonetheless, they have the power to delight. Once, I got about ten pages into a turgid sword-and-sandals screenplay, all cod-medieval language and leather-jerkined beefcake. I was losing my mind. Then, on p.11, zombies lurched over the hill and started tearing everything in this uninspired, generic narrative world into pieces. It was great. I enjoyed reading that screenplay from then on in. Since that day, I’ve turned many a page hoping for those zombies to return, hoping that they might burst into the cozy emotional drama and rip the heads off the insufferably passive protagonist and his insipid girlfriend before laying waste to the entire smug family. I’m hoping that the writer is bold enough to introduce a dynamic element – not necessarily actual zombies – that will escalate the stakes, slam the protagonist into extreme jeopardy and get me pounding through the remaining pages because I have no idea how she’s going to make it out alive by the end. Unfortunately, it never happens. Most screenplays lack what I identify as the Z-factor.

FIX: Ask yourself (or your beta-readers), would my screenplay be more fun, more exciting, more vital, more likely to tickle the fancy of a jaded reader if I suddenly introduced a pack of marauding zombies? Or would the ambulatory dead prove an irritating distraction from the compelling story I’ve already got going on? If your narrative lacks the Z-factor you need to find a way of adding it, or rip your screenplay up and start again.

It's hard out there for a screenwriter. These are just my pet peeves - every reader is different. If you read a lot of screenplays, what has you reaching for the liquor (or gun) cabinet when you see it on the page?

About the author

Karina Wilson is a British writer based in Los Angeles. As a screenwriter and story consultant she tends to specialize in horror movies and romcoms (it's all genre, right?) but has also made her mark on countless, diverse feature films over the past decade, from indies to the A-list. She is currently polishing off her first novel, Exeme, and you can read more about that endeavor here .