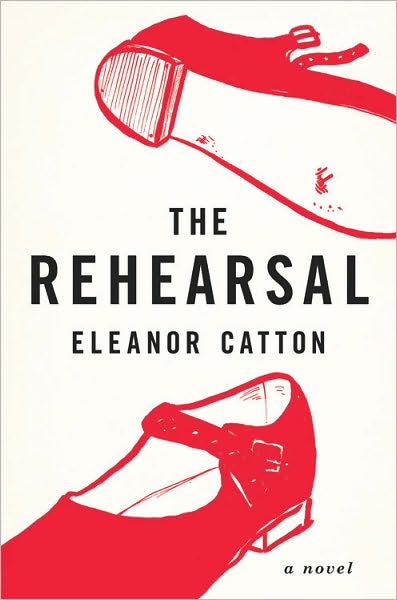

Look at this book:

Mentally project said book onto a shelf as you walk by. Assume your eyes flicker to it. Does it appeal? Would you reach up (in my hypothetical situation, you are short or the shelf is high) to read the back copy, maybe flick through the pages?

If you answered yes, you and I differ. My girlfriend recommended the book to me with great enthusiasm, saying it was the exact kind of writing I would enjoy. A quick Google brought up that cover. Surely this was emphatically not my kind of book. This was not even "proper" literature. A woman (only seen from the neck down) all in green, leaning back against a row of cabinets. Cliche upon cliche; I thought of that dreaded epithet: "Chick-Lit". Not only a mass-marketed pulpy waste of time, but one specifically designed not to appeal to my gender. There's nothing inherently wrong with any genre, even teen supernatural romance, but with so few years to spend cracking spines (of books) and tearing through pages (again, in books. Not ushers), could I really waste time attempting a book like this?

Now, I'm amplifying my snobbery a little. All these thoughts were knee-jerk, occurring in the five seconds after first seeing this cover. "Don't judge a book by its cover" – one of the cliches that is so cliched, most people would wince if anyone in their vicinity offered it as serious food for thought. Even so, what a hard habit to break.

I read Eleanor Catton's book. It's one of the most haunting novels I've read in the last year. A sex scandal is a catalyst for a strange and charged friendship between two girls at an Australian school. Teenagers become aware of their bodies, the potency of said bodies, and the borders between reality and performance begin to drain. As all of this culminates, the all-knowing saxophone teacher plays her students off each other, her intentions mysterious and possibly malevolent. It's a wonderful novel. Eleanor Catton was in her early twenties when she wrote this for her Master's thesis. Damn her. The chasm between what I expected from this book, with its trite and inappropriate cover (though how, having heard a rough synopsis, would you capture the novel in an appealing and original image?) highlighted a real problem: many women writers are writing incredible books, boundary pushing and transgressive in the real sense, but are left spiraling out of reach from readers who would love their work. This is a well-documented problem, but it's easy to fall into that old cognitive trap: I'm a diligent reader, knowledgeable of such things. That won't happen to me. The Rehearsal revealed my foolishness.

It's a great book, and I urge you to give it a try. The US cover is a little better but still hardly representative of the greatness within:

This is an issue affecting fiction written by women. The reasons are many, intricate and explained far better that I could hope to by more learned people. Meg Wolitzer, herself a well-respected novelist with "chick-lit" covers, writes at length about this categorization of literary writers cast down into the limbo of "women's fiction". Authors are swaddled together with no regard to plot, themes, character or prose style. All they have in common is their gender. The covers are ambassadors of this faux-taxonomy, presumably disregarding the contents in a desperate scrabble to filch the odd susceptible consumer looking for a light read. As Wolitzer puts it:

These covers might as well have a hex sign slapped on them, along with the words: “Stay away, men! Go read Cormac McCarthy instead!

A brief caveat: these issues are not new or undiscussed. I don't want this to be the patronizing ramblings of a white middle-class man who's discovered that, hey, the other gender can write too. Obviously. A large network of reasons and factors are at play here, far more than there is room for in this piece. What matters is our imagining ourselves as above this somehow.

With this in mind, what are we missing? Furthermore, it's impossible to read everything anyway. Who cares?

Here is something that embarrasses me: I'm a white middle-class male with liberal views and hope to be devoid of bigotry: yet the ratio of books by male to female authors is roughly 9:1. Certainly this is not intentional. In trying to think out how exactly my reading was so lopsided, one thought occurred to me: I've always loved the rambling, nonlinear and baggy novels, the magnum opuses like Gravity's Rainbow, 2666 and Ulysses. Those have always been the glorious pinnacles of literature for me. And, foolishly, I couldn't name a single woman writer who delivered these kinds of things. Not that I'd been looking. I didn't think I needed to.

In fact, I can only think of one female-authored work in the vein of the above, large experimental works: Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebook- that obscure work that, uh, is on almost every list of greatest novels and inspired generations of women in the sixties and beyond. The one that changes time, characters and modes of storytelling between chapters. Communism, loneliness, masculinity and artistic failure all invoked perfectly. Achingly beautiful prose, both true to life and dreamlike. This book that everyone called a masterpiece fifty years ago and are still calling a masterpiece has turned out to be a masterpiece. Doris Lessing is hugely well-respected (as is this book, usually considered her greatest) and won the Nobel Prize in 2007. Despite this, I had never attempted this book, even though it exactly matched the criteria for books I love.

This is exactly the problem with fiction by women being hamstrung by poor covers and marketing. It goes beyond us, the readers, being refused quality books. The Golden Notebook is the anomaly, a great ambitious and cerebral book that slipped through. It is assumed that, for whatever reason, you will not buy a "grand opus" if it is by a woman. Regardless of your gender, if you are a decent human being that should bother you. Whatever your personal views and beliefs, you are being treated as if you are sexist. Furthermore, what is signified by the term "chick-lit"? I think of pink and glitter, shopping and shoes spoke of in rhapsodic hyperbole, and the trials of attracting and dating men. Women: this is what your culture thinks defines you. This is your quick summary, how you'd be labeled on the bottle.

Follow it down the rabbit-hole, and the concern about bad book covers traces back to the central issue that, for all recent strides, bullshit stereotypes – harmful stereotypes – still exist. And crap begets crap. What great works can arise if books by women are only sold to an imagined female reader, only interested in "women's things"? If great novels, ambitious and daring, are neutered and forced to compromise or pray for readership on a tiny press? Again: these books do exist. They're just hidden behind ugly covers and cowardly marketing.

But it needs to go further. Otherwise there can be no hope for the true transgressive woman writer, the female Georges Bataille or William Burroughs. Naturally, there are plenty of examples of woman writers that do transgress and take literature to new and exciting terrains. (One even teaches here; the supremely amazing author Lidia Yuknavitch.) Yet, for now, the canon is rarely altered. Doris Lessing's masterwork is accepted, but few other similarly ambitious works make the cut. Gertrude Stein might hover around the fringes. Kathy Acker's work has a devout following, but is rarely esteemed to the levels of her male equivalents.

As I said, these books are out there. I've spent the last few months seeking them. Real eerie and outlandish works by women that, while finding much-deserved fans, may often be ignored by the wider readership. Amelia Gray's Threats (justifiably gaining momentum – and look at that awesome cover!) unsettles with a few choice sinister words scrawled on paper, and the mental decay of a recent widower (or is he?). Ali Smith's There But For The dissects the nature of fame, loneliness and connectivity in a strange novel about a dinner party guest who locks himself in the spare bedroom and refuses to leave. Books like these deserve to be read. Right now I'm 100 pages into Nicola Barker's Darkmans. A young boy is possessed by the ghost of a court jester and THAT'S NOT JUST HAPPENING IN THE BACKGROUND. I'm in love.

To repeat: I'm not an expert. Nor do I have answers. I'm merely hoping that my unintentional ignorance serves as a suggestion, and a warning. By their nature, experimental and strange books are marginalized enough. If transgressive fiction has a duty to go beyond literature and affect the real world then, here, please, let it transgress.

Photo from PrintMag

About the author

Jack is a graduate of the University of Warwick. His current project is a surreal biography of the band Paris and the Hiltons. He lives in the UK, where he founded the netlabel Portnoy Records. He can't juggle yet, but really is trying very hard. Often he tells people he's ten feet tall, even when they're standing in front of him, which makes for awkward pauses. He writes incoherent thoughts and opinions at the International Society of Ontolinguists.