Return of the Son of Twilight Zone: Dusk as a Theme

Just as I’m happiest in the autumn months, so dusk is my favourite time of day. It’s a time when objects, thought and feelings lose focus: the light gives way, yet darkness has not yet taken control. Because of this ambiguity, dusk can be difficult to describe in words, and it might well be this difficulty which has drawn many poets and novelists towards it as a subject matter. Here is the paradox: if dusk is described too exactly, it loses its essential nature.

In scientific terms, dusk happens when the sun has dipped below the horizon line, but its rays are reflected and scattered by the atmosphere sufficiently to bring us the soft, suffuse colours of twilight. In fact, there are three periods of twilight, from brightest to darkest: civil, nautical and astronomical. In this period, everything takes on a softer tone, words fade on the page, vehicles switch on their headlamps, various animals and plants are roused from their daytime sleep, artificial lighting systems are triggered in the streets and housing estates. And new ideas are triggered in the brain. The night awaits us with its promises, and fears. Now people feel they can more easily whisper secrets to each other.

Here’s Elizabeth Gaskell, from her novel of 1855, North and South: “There was a filmy veil of soft dull mist obscuring, but not hiding, all objects, giving them a lilac hue, for the sun had not yet fully set...”

As any science fiction fan knows, the Twilight Zone also represents those aspects of our lives and psyches that can barely be understood: here the weird creatures and phantoms of the id gather. Many artists have been tempted by dusk’s nebulous properties: painters such as de Chirico, Monet and Turner; composers like Debussy, Delius, and Schubert; photographers such as Bill Henson and Gregory Crewdson. The Romantic era especially was full of twilight fantasies; it was seen as the time of secret assignations and trysts. And of seductions. If night is when we actually proceed with our plans for romantic, sexual, or even criminal activity, then dusk is the time of planning, of imagining future events. Now everything is held in balance; the moment suspended. From this sense of expectation, dusk draws its potency.

I love to watch the fine mist of the night come on,

I love to watch the fine mist of the night come on,

The windows and the stars illumined, one by one,

The rivers of dark smoke pour upward lazily,

And the moon rise and turn them silver...

– Charles Baudelaire, Le Fleurs de Mal, 1857

Some words from the scrapbook: dusk, twilight, the gloaming, the gloom, evenfall, eventide (so lovely with its sense of darkness creeping forward over the land), sunset, sunfall, sundown, moonrise, crepusculum (Latin), crepuscule (French), crepuscolo (Italian/Spanish), dämmerung (German). Dusk also gives birth to the rather beautiful verb: dusking. “Upon her fair face the evening sky was slowly dusking...” An old dialect word from Devon is dimmet. “It was dimmet when young Thomas sallied forth upon the moorlands...” In Cornwall they have the word dimpsey, which actually sounds like a place name. Which is just what dusk becomes in A Man of Shadows: a place rather than a time, a tract of lost and barren land situated between the twin cities of Dayzone and Nocturna. Accordingly, the residents of Dayzone usually capitalise the word: Dusk. Or they call it the duskfold, or the fogline, or the realm of Hesperus, the first star of evening. And it’s seen above all as a place of fears, of nightmares. One character calls it the subconscious of the city. It is a place of mystery, of mist, shadows, vaguely glimpsed people and entities, of whispers, far-off animal cries, and ghostly disembodied voices. In a foggy, weed-strewn car park, a grand piano emerges from the gloom...

In 1957, jazz pianist and composer Thelonius Monk went to visit his wife Nellie in hospital, where she was undergoing treatment for a thyroid disorder. After the visit, he was moved to write a new melody for her, which he called “Twilight with Nellie”. After hearing the tune, Monk’s patron of the time – one Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter – persuaded him to use a French term in the title. And so one of Monk’s most beautiful ballads was born: “Crepuscule With Nellie”. In fact, the very first draft of my novel was given this same title: Crepuscule With Nellie. I had in mind that I would write a series of weird murder mysteries, each taking a Monk tune as its title. There were so many good ones to choose from: “Ruby My Dear”, “Criss Cross”, “Misterioso”, “Straight No Chaser”, “Round Midnight”, “Little Rootie Tootie”, and so on. That idea fell away in time, leaving only one thing behind. I’d learned that Nellie can be a shortened form for a number of different girl’s names, among them Helen, Ellen, and Eleanor. And so the female protagonist of the novel is called Eleanor.

When all my will is gone you hold me sway

I need you at the dimming off the day.

–Richard & Linda Thompson, 1975.

A few years ago, the Victoria & Albert Museum put on an exhibition entitled “Twilight: Photography in the Magic Hour”. I went along, seeking inspiration, and was introduced to the work of the already mentioned Henson and Crewdson, two amazing photographers of the strange and unnerving events that can take place at dusk. Their imagery proved to be very influential on the book’s early progress. At the exhibition I also learned of an intriguing French phrase used to describe twilight: entre chien et loup. This refers to that time of day when it’s difficult to distinguish between a dog and a wolf, between friend and foe, the benign and the dangerous. And so for a time the novel was called Between Dog and Wolf. The phrase still exists in the book as a chapter title. I like to think it represents the inner struggles of my detective hero, John Henry Nyquist, as he battles to perform a good deed in a bad world, against his instincts, and his fears.

There’s yet another way to see dusk, in terms of approaching death. Here’s Shakespeare, in his seventy-third sonnet:

In me thou seest the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

Yet this period of transition also brings forth its own particular kind of life. Just as there are diurnal plants, and nocturnal animals, so there are flowers that bloom in twilight and creatures that become active around sunset. For a brief period these crepuscular lifeforms hold sway. Fireflies light their bodies up and take to the air. Certain species of bat spread their wings. Small mammals snuffle through the undergrowth. Snakes unwind themselves in this magical, perfect time, when the temperature is poised between hot and cold, exactly right for their activities. The sun lowers further. The light is violet-tinged. A cloud of midges plague the man and woman walking home along the lakeside path. Purple coloured flowers open up under moonlight, to be pollinated by moths. All this is good, strong, rich imagery. And, because of the sorry way my mind works, those moon-blossomed flowers must hold within their petals a drug, an opiate of some kind. Baudelaire would’ve approved, I hope, of these newly formed flowers of evil: the poppies of twilight.

My favourite dusk poem of all is “The Warning”, a five line masterpiece written around 1910 by the incredibly obscure – and rather unfortunately named – Adelaide Crapsey.

Just now,

Out of the strange

Still dusk... as strange, as still...

A white moth flew. Why I am grown

So cold?

Poor Adelaide lived, worked and died (at the age of thirty-six) in a tragic, twilight realm of her own, her poems hidden from view by the same mist that she so often conjures up in her work. Yet I like to think that the “strange, still dusk” called to me as well, as I wrote A Man of Shadows, as I followed private eye John Nyquist across the borderline into Dusk.

Read part 4 HERE

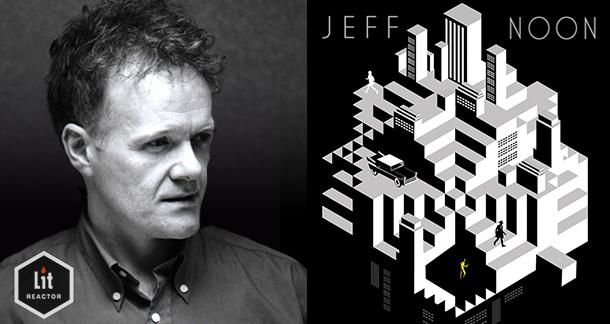

Get A Man of Shadows at Bookshop or Amazon

Get The Complete Sonnets and Poems of Shakespeare at Amazon

To leave a commentLogin with Facebook