Ever had the experience of reading a fantastic book and wishing someone could make a film of it? Ever had the experience of seeing that film and wishing you could maroon the director on a very small island with only Rush Limbaugh for company? In the spirit of being careful what you wish for, here are five book to film adaptations which had me choking on my popcorn and wondering how anyone could take something so good and end up with something so…there’s no other word for it…crap.

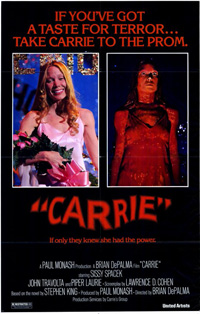

'Carrie' by Stephen King

'Carrie' by Stephen King

The story of Carrie’s publication is a story in itself – High School teacher, struggling to make ends meet, first pages of manuscript dumped in the trash, recovered by wife who insists he finish it. King was so poor when he sold his first novel that his phone was disconnected to save money and his editor had to contact him by telegram to give him the good news.

The rest, as they say, is history. Carrie the book went stellar, selling over 16 million copies and King was on his way to becoming one of the bestselling authors on the planet. A mere two years later, King’s chiller about a girl with telekinetic powers who takes a terrible revenge on the High School bullies who torment her was adapted for the screen by Lawrence D. Cohen and Brian De Palma. The film opened just after Halloween in 1976, to rave reviews and queues around the block. From a cast of then-unknowns, it made household names out of Sissy Spacek, Amy Irving, William Katt and (probably most famously) John Travolta. Quentin Tarantino loves it. It’s one of the most-watched horror films at Halloween. It’s also one of the only horror films to get a couple of Oscar nods – for Spacek and Piper Laurie.

And yet I hate it.

The freshness and originality of Carrie the book lies in King’s approach to the telling of the story. He uses the technique of false documents – extracts from a book purportedly written by one of the survivors, witness statements, letters between families – which give the narrative a sense of chilling possibility and also root the tale firmly in the small town/rural poor territory for which King would become famous. The letter at the end of the book, where a relative of the White family describes seeing her daughter display similar powers to Carrie –mis-spelt, barely articulate - is both moving and scarily realistic.

All of that is lost in the film. De Palma’s production is stagy, ponderous and badly acted. Realism is the last effect De Palma was after – his is a High School of adults taught by adults, Piper Laurie is improbably attractive as Carrie’s insane mother, his moral center the numb-looking Katt and Irving (who looks like she can barely keep her eyes open much of the time). Watch it again, without the accompanying hype, without its pedigree in mind and you find yourself watching a third rate shlock. Scenes are allowed to continue past the point of boredom and into hilarity (check out the part where gym coach Betty Buckley punishes Carrie’s tormentors with boot camp training and we are treated to five solid minutes of her shapely thighs while girls in short-shorts do burpees). Even the key ‘prom’ scene underlines its points with the filmic equivalent of black marker pen. There isn’t a single image we’re allowed to construct ourselves, no moment where what we are supposed to be thinking and feeling isn’t presented to us on a plate. King’s realism, his sympathy for the abused girl, his teasing out of the lasting impact of the tragedy, vanishes into a welter of pig’s blood and tricksy split-screen moments.

[amazon 0671039725 inline]

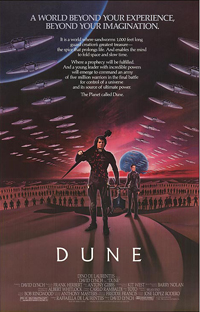

'Dune' by Frank Herbert

'Dune' by Frank Herbert

I have to admit to a sneaking liking for the fated, hated film adaptation of Herbert’s epic. David Lynch, always one to inject a sneaky subversive vibe into his work, manages to both totally miss the point of the book and give us some scenes of a queasy nastiness to rival Dennis Hopper and his tank of nitrous oxide in Blue Velvet. But if watching Kenneth McMillan as Baron Valdimir Harkonnen taking time off from having his boils lanced to rip the heart plugs out of hapless underlings isn’t your beverage of choice, you might find the rest of the film a tad…confusing.

Dune the book is – to cram the work into a very tight nutshell – Game of Thrones with technology. It’s all about dynasties, plots and the battle for control of a scarce resource: in this case a substance called ‘melange’ - mind altering, capable of folding space-time and only found on the desert planet Arrakis. Herbert’s huge, multi-layered story combines ideas from the then-nascent environmental movement with political, religious and even psychodynamic themes (Jung was an influence) to create a world which is as complex and satisfying a fictional Universe as you are likely to find between the covers of a book.

And to be fair to Lynch, attempting to get all of that into a single film would tax the abilities of the most talented of film makers. Sticking to the Game of Thrones comparison, the first book of George R R Martin’s series was adapted into ten episodes of an hour each. Set that against Dune’s eventual running time of two hours and forty minutes (and that after extensive cuts by the studio) and you begin to see the problem. Just explaining the story takes almost that time, never mind allowing for some character development and a bit of sandworm action. But I suspect that even if Lynch had been given the mini-series Dune deserved (and eventually received courtesy of the Sci-Fi Channel) he would have dumped the plot in favor of the Harkonnen excesses. Lynch, a visual director par excellence, wouldn’t have been able to resist the lure of Herbert’s rich descriptions of the immensely fat Vladimir and his exquisitely wrought cruelties.

Since Lynch’s magnificent failure, attempts to remake the film have all stalled, most recently in 2011 when Paramount was the latest studio to take on Dune and lose.

[amazon 0441013597 inline]

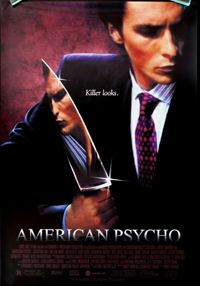

'American Psycho' by Bret Easton Ellis

'American Psycho' by Bret Easton Ellis

For some, objections about American Psycho’s adaptation into a film isn’t about the quality of the cinematic result, or whether the movie manages to capture the essence of the book. It’s about finding the original work so objectionable that the thought of giving it visual expression is repellent in and of itself.

The passage of Easton Ellis’ third novel to publication was stormy. Simon and Schuster, his then-publishers, dropped the book after protests from women’s organizations at its graphic depictions of torture and sexual sadism. It was picked up by Random House and achieved immediate and almost-inevitable cult status, plus highly respectable main-stream sales as the book buying public rushed to assuage its curiosity about what exactly the fuss was about.

Since then, Psycho has inspired many column inches of analysis. It’s an exploration of anomie, of the emptiness engendered by an existence based on the consumerist ethos, where who you know and what you wear are the currency that defines you. Patrick Bateman, Easton Ellis’ now famous protagonist, tries to wrest meaning from his world with his killing sprees - the tortures he inflicts on his victims set out with the same meticulous detail as when he notes the outfits of his work colleagues or details his exercise routines. When your life is composed of lists, Easton Ellis seems to be telling us, it doesn’t much matter whether it’s clothes or music or body parts you’re bullet-pointing. Deprived of emotional content, one thing (a cotton oxford shirt by Ralph Lauren) is much like another (hands swollen to the size of footballs). And the proof of this thesis is demonstrated by the deaf ear Bateman’s friends and family turn to his confessions. They literally can’t hear what he’s telling them, because in their world of objects, a shirt really does have exactly the same emotional status as a dead woman.

American Psycho is a book of ideas, a worthy (if stomach turning) addition to a genre amongst which you might include J.G Ballard’s Crash, A Clockwork Orange and David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest. And this is why the film version of the book, which premiered in 2000, was doomed to fail. What works in print - the to-do lists, the excursions into music, the deconstruction of an outfit, the incantation of purchases – can’t work on film. Seeing a murder doesn’t have the same emotional distance as reading about it, and seeing the same murder committed over and over again eventually becomes torture porn. Mary Harron, the director, may have intended American Psycho to present the book’s message as a modern comedy of manners, but it was a message which could only be conveyed in one medium: the printed word.

[amazon 0679735771 inline]

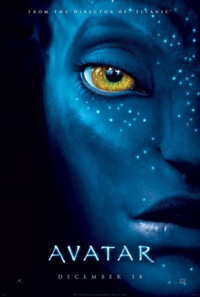

'The Word for World is Forest' by Ursula K Le Guin

'The Word for World is Forest' by Ursula K Le Guin

Ursula Le Guin, probably best known for the Earthsea trilogy, produced her delicate, intellectual novel The Word for World is Forest in 1976. The book tells the story of an ill-fated attempt by human loggers to exploit the forests of the planet Athshe. Despite instructions to treat the native population with respect, the soldiers guarding the new colonies soon begin to rape and enslave the Athsheans. The peaceful humanoids are connected via a system of lucid dreaming – in fact the whole planet acts as one organism – and pushed too far, they unite and exact revenge on the humans, eventually forcing them to leave.

When asked about the origins of Avatar James Cameron never explicitly referenced Le Guin’s novel and you have to hope that the omission was ingenuous, because when you read the book, the similarity in characterization and plot to Cameron's film are startling. At least one character: Cameron's power crazy Na'vi slaughtering Quaritch, is practically indistinguishable from Le Guin’s power crazy, Athshean-slaughtering Davidson (who comes to an unpleasant and well deserved end at the hands of the people he enslaves). Like the Na’vi, the Athsheans have a connection with their environment which goes much deeper than anything a human can experience and like the world Cameron creates in his film, Pandora consists of organisms which are interdependent in an ineffable, almost spiritual way.

And even if the film isn’t acknowledged as an adaptation of the book, it’s still painful to read Le Guin’s masterfully spare prose in which she manages to conjure up worlds, variant species of humans, several different philosophies and a suite of intriguing technologies and compare it with the blue-painted, bloated, ear deafening monstrosity it became on screen. The environmental message, skillfully underplayed by Le Guin in her book, is presented in Avatar with all the finesse of a custard pie in the face. It’s as though Cameron doesn’t trust us to understand his message unless he screams it at us at the top of his voice, and while film is (to my mind at least) a much less subtle medium than writing, it is possible to get a point across (in this case that humans must constantly fight their tendency to ruthlessly exploit every resource which comes their way) without slapping the audience upside the head with it.

[amazon 0765324644 inline]

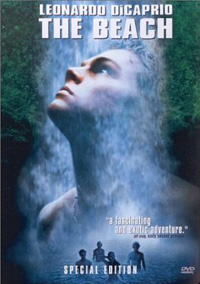

'The Beach' by Alex Garland

'The Beach' by Alex Garland

This book probably needs no introduction: it topped the best seller charts when published back in 1996 and entered the collective cultural psyche four years later when Leonardo DiCaprio, still riding high after Titanic, signed up to play the lead in the film version. The idea of DiCaprio disporting himself in swimshorts excited the hormones of many a young female fan, as it was no doubt intended to do. Eagerly anticipated, The Beach (film) proved to be a huge disappointment and not just to damp-knickered teens. Fans of the book were also downcast by the adaptation and DiCaprio’s performance was judged so awful, it was Razzie nominated that year (lucky for DiCaprio, 2000 was a good year for bad performances: John Travolta won for Battlefield Earth).

But why? How did Danny Boyle, director of Trainspotting, manage to turn Garland’s cult book about an idyllic community on a far flung Thai island into a gobbling turkey so massive that even the hugely popular Moby soundtrack couldn’t rescue it?

The problem lies in tone. Garland’s book, narrated by main character Richard, is a textbook exercise in voice. Richard – refugee from normality, secret romantic and gullible wide eyed cynic – populates the story with observations that will ring entirely true with anyone who has spent more than five minutes in the company of the average backpacker. The way Garland writes Richard not only makes the character believable, it gives all the events in the book a sense of inevitability. Only someone like Richard – whose world weariness is untempered by any hint of real experience – could stumble into a setting as inbred and explosive as the Beach and not see disaster looming like storm clouds on the horizon.

But all of that is lost in the film. DiCaprio’s Richard is a sensation seeker, not a traveler. He doesn’t have the right stoner roots: the doped out, gamer sensibility that permeates Richard’s every thought process in the book. DiCaprio is too clean, too smart, too clued in. When he arrives on the Beach it’s impossible to believe he wouldn’t take the first raft out again, even with the delectable Virginie Ledoyen to tempt him to stay. Without book-Richard’s unworldliness to motivate the situation, the plot of the film version collapses under the weight of its own improbability. What we're left with is nothing more than a so-so thriller.

[amazon 1573226521 inline]

But these are only my choices and one thing I do know from late night bull sessions is that everyone has their own list of great books that made crap films. Which book did you love only to wince at the film adaptation? And if they had bothered to ask you (weird how they never do) – what would you have done differently?

About the author

Cath Murphy is Review Editor at LitReactor.com and cohost of the Unprintable podcast. Together with the fabulous Eve Harvey she also talks about slightly naughty stuff at the Domestic Hell blog and podcast.

Three words to describe Cath: mature, irresponsible, contradictory, unreliable...oh...that's four.