Where Is All the Feminist Vampire Literature?

The word ‘vampire’ conjures images of Lestat, Edward Cullen, and Dracula; men whose cursed nature causes them to commit acts of bloodlust that are at once violent and euphemistically sexual. Sure, there are some powerful female figures in vampire literature and lore as well—there’s the 1872 novella, Carmilla, for instance, which predated Bram Stoker’s Dracula by over two decades. There have also been opportunities for modern vampire novels to catch fire with the public consciousness in books like Octavia Butler’s Fledging and The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez, which follows a young woman who becomes a vampire while working in a brothel. They’ve enjoyed attention and critical praise, but it’s arguably difficult to shake the notion of ‘vampire’ as fundamentally masculine.

It would be easy to pass the reason for this off as the vampire myth being rooted so firmly to the archetype of Dracula. What immediately comes to your mind when you hear the word ‘vampire?’ For me, my first association will probably always be Bela Lugosi, and I doubt if I'm alone in that connection. After all, Dracula is the character who popularized vampire fiction to a mass audience and it’s hard to separate his shadow from the rest of the subgenre. And to be perfectly clear, I’m not here to stake Dracula. I gave a passing minute of thought to the gendering of vampires one autumn day and wondered…why? Is there a deeper reason why the most culturally pervasive bloodsuckers seem to be men?

Escaping chrononormativity

As it turns out, there’s some fascinating analysis written on this topic. “The Vampire, the Queer, and the Girl: Reflections on the Politics and Ethics of Immortality’s Gendering” by Kimberly J. Lau dives into the relationship between the vampire and “chrononormativity,” a term used in her essay and other scholarship to define “the hegemonic temporal order that undergirds ‘genealogies of descent and the mundane workings of domestic life’ while also ‘organizing’ individual human bodies toward maximum productivity.’”

Essentially, there is an expectation that life follows a teleological pattern of marriage, having offspring of one’s own, old age, and death.These benchmarkers assign definitions to our collective notions of what life is. Vampires, however, spit in the face of all of these “human” benchmarks and demonstrate an alternative mode of existence. This “recursive as opposed to progressive genealogy—brings a formal dimension to bear on the question of how queerness operates in and through the genre in ways that continually chafe against dominant ideologies of time and power as well as time’s power.”

Essentially, there is an expectation that life follows a teleological pattern of marriage, having offspring of one’s own, old age, and death.These benchmarkers assign definitions to our collective notions of what life is. Vampires, however, spit in the face of all of these “human” benchmarks and demonstrate an alternative mode of existence. This “recursive as opposed to progressive genealogy—brings a formal dimension to bear on the question of how queerness operates in and through the genre in ways that continually chafe against dominant ideologies of time and power as well as time’s power.”

In the same vein (haha, vampire pun), immortality interrupts the chrononormativity of the expected life cycle for women as child bearers even more noticeably than their male counterparts. The vampire represents nonreproductive sexuality, and there’s a much larger body of academic work and studies out there examining the notion of a sexual double standard that has long awarded men a greater degree of sexual freedom and enjoyment, possibly making the disruption of chrononormativity an easier pill to swallow for male versus female characters. As Lau points out, some of the earliest English vampire fiction was a Byronic fragment with queer undertones about a young man who became fascinated by an older man while on tour of the Continent; women of the time were frequently restricted by domestic expectations and not allowed the mobility that might lead to such a life-altering encounter.

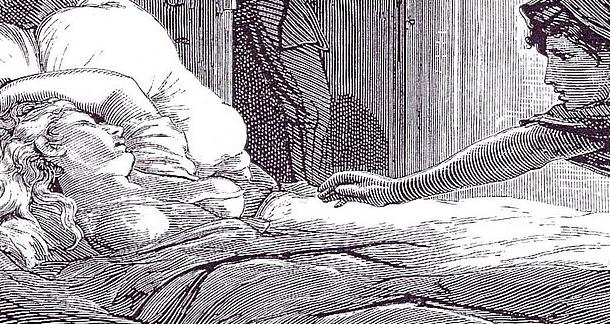

The Victorian tale of Carmilla, for instance, concerns the physical relationship between two women at a time when such relationships were completely taboo in the society in which the literature was being circulated. Past analysis of Carmilla by Colleen Damman states that “as a woman, Carmilla can only claim her sexuality after death. Thus, vampirism is the only way she can express her own carnal desires. Besides marriage, becoming a vampire is one of the only ways that female sexuality is licensed in the Victorian era.”

An experience outside of patriarchal authority

So where does this bring us to in the modern day? What does the female vampire mean now? Surely we’ve moved past the Victorian standards of a repressive sexual binary that drew out some of the earliest English language vampire tales? (I’ll let you answer that question for yourself, reader. The overturning of Roe v. Wade leads me to believe that there’s still some tension over the idea of handing the reins of the teleological narrative over to women).

The vampire’s life outside of death represents “an experience that exists outside patriarchal authority,” thus the general unease surrounding feminist vampire literature, which takes the female character outside of reproductive futurism. Lau argues that vampire fiction represents a “double standard that promises an uncontainable queer surplus for male vampires but a constant return to the patriarchal order for female vampires whose legacies grow out of the canonical English-language vampire narrative.” She points out that even when female vampires are coupled with male partners, their inability to bear children represents “a queer heterosexuality—a union eternally resistant to reproduction, always already positioned against reproductive futurism—and this results in their cultural invisibility.”

This could explain some of why the narrative of the Twilight series felt so ineffective; in her quest to become an immortal vampire, the main character, Bella, also rushes to collect a husband and has a half-vampire child, following all of the teleological human goal posts to the letter before then (seemingly) being released into a kind of delayed afterlife. Lau also writes that “the vampire narrative as simultaneously fantasy literature and cultural fantasy exposes the limits of hegemonic life/time and raises questions about what might be possible if we think creatively and expansively about living ‘in excess of the real.’” I love that phrasing, because it brims with possibility for horror as a genre.

This is by no means an expansive discourse on the topic of feminism and vampire literature. Are there vampire stories out there that should be a critical part of this thread of discourse? What would you like to see in new vampire fiction? Let us know in the comments.

Get Fledgling by Octavia Butler at Bookshop or Amazon

To leave a commentLogin with Facebook