The Life and Death of Richard Bachman

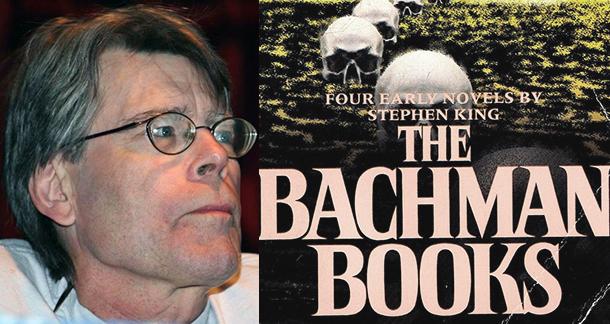

Photo via Pinguino

For a period of eight years in the late ’70s and early ’80s, a writer named Richard Bachman existed. His novels, the first four published exclusively in paperback, did not find themselves placed at the top of any bestseller lists. Steadily, Bachman managed to attract a small fanbase. Rumors of a conspiracy didn’t take long to surface. Early on in Bachman’s career, readers wrote letters addressed to horror icon Stephen King with one simple question: “Yo, is this motherfucker really you? If not, he’s totally ripping you off.” King was quick to deny these rumors, although the writing styles of both authors were inarguably similar. Of course, any fan of the horror genre today should already be well aware of the accuracy of these suspicions. Richard “Dicky” Bachman was, indeed, King’s pseudonym. But was he more than just a clever disguise? Was he, perhaps, Stephen King’s darker half?

According to King, Richard Bachman started as an outlet to release a couple early books written before Carrie that he felt readers might enjoy, but the pseudonym soon become something much more meaningful. Bachman took on a voice of his own and found the type of career King himself often craved. Bachman was a recluse. He did not make special appearances. He did not accept interview invitations. He wrote the books he wanted to write and he moved on. He didn’t sell enough copies for the media to hound him but he did sell enough for a man to make a living on.

From King’s essay, “The Importance of Bachman”:

“[Richard Bachman] began to grow and come alive, as the creatures of a writer’s imagination so frequently do. I began to imagine his life as a dairy farmer…his wife, the beautiful Claudia Inez Bachman…his solitary New Hampshire mornings, spent milking the cows, getting in the wood, and thinking about his stories…his evenings spent writing these stories, always with a glass of whiskey beside his Olivetti typewriter.”

King created an entire backstory for Bachman, details leaked in publicity dispatches and the short author bios found at the end of his books. He gave Bachman life. He gave him his own tragedies. He gave him a son and he took that son away by making him drown in a well. He gave Bachman a brain tumor and then he cured him. A god manic with power.

Of course, Richard Bachman was not King’s first choice for a name. Originally, his pseudonym was going to be “Guy Pillsbury”—after King’s own grandfather—but at the very last minute before Rage’s release someone caught wind of the shenanigans, so King quickly came up with a new name. At the time, he was reading a Richard Stark novel (another famous case of pseudonymitis) and listening to Bachman-Turner Overdrive. Easy peasy.

RAGE

Bachman first came onto the scene in 1977 with Rage, a short novel about a school shooting. Like the majority of the titles released under Bachman’s name, the writing was tight with little-to-no padding. His prose didn’t beat around the bush with its assault. It came directly for you like a countdown clock seconds from expiration. One punch after another until you were too weak to stand and crumbled to the ground. Rage, originally titled Getting It On (lol), is perhaps one of King’s earliest works. He started on the manuscript in 1966 while still a high school senior. He would later stumble across it again four years later and finally complete it in 1971. It was released in 1977 under the aforementioned pseudonym, only a mere three years after the publication of Carrie. Much like King when he first started the novel, Rage focused on a high school senior named Charlie Decker. After receiving word that he’s been expelled, Decker retrieves a handgun from his locker, then shoots his algebra teacher. While the rest of the school evacuates, Decker holds his math class hostage as he fucks with police negotiators outside the school. Rage does not mess around. It’s flawed and unforgiving. There has never been a more accurate title for a book. The title not only describes the story, but the author’s style as well. Richard Bachman read like a man perpetually pissed off and desperate for a way to set the whole goddamn planet on fire.

It’s understandable then that many other high school seniors might have been able to relate to the angst found in Rage’s Charlie Decker. Which is why, in the final years of the twentieth century, King requested for the novel to be removed from print. In 1988, eleven years after Rage’s publication and four years after Bachman’s outing, a senior at a California high school held his humanities class hostage for a half hour with a semi-automatic. It was reported by the kid’s friend that he’d been obsessed with Rage, having read it over and over. Then, one year later, a Kentucky high school senior took a history classroom hostage for nine hours with a shotgun and two pistols. Police later found a copy of Rage in the perpetrator’s bedroom. In 1993, another Kentucky high school student wrote an essay about Bachman’s novel. His teacher gave the essay a poor grade. A few days later, the student killed both his teacher and a custodian with a revolver, then held his class hostage for a short time before releasing them. Then, in 1997, a fourteen-year-old boy killed and injured multiple students involved in a youth prayer group. A copy of Rage was discovered in his locker. After this last incident, King pulled the plug and allowed it to go out of print. Of course, it’s argued that King made the wrong decision and should not have blamed himself. Others praise him for attempting to prevent further shootings. In any case, nobody is more troubled by the book than King himself.

From “The Importance of Bachman”:

“If there is anyone out there reading this who feels an urge to pick up a gun and emulate Charlie Decker, don’t be an asshole. Pick up a pen, instead. Or a pick and shovel. Or any damned thing. Violence is like poison ivy—the more you scratch it, the more it spreads.”

I recommend this article by Peter Derk for a more in-depth debate on the matter.

THE LONG WALK

Bachman’s sophomore release arrived in 1979, although it was the first novel Stephen King had ever written (that was ever published, at least). A freshman in college, King submitted his recently finished manuscript to Random House’s first-novel competition. Sent in return was a standard form rejection. Depressed, King stashed the novel away and didn’t bother sending it out again until, over a decade later, New American Library asked for a follow-up to Rage.

The Long Walk might be my favorite book King ever wrote. I could spend a lot of time here explaining my reasons, but George Cotronis kind of already did exactly that in his LitReactor article. I agree with everything he says here. The Long Walk is perfect in every possible way.

ROADWORK

Written between ’Salem’s Lot and The Shining, Roadwork was King’s attempt at writing “a straight novel.” He was young and feared hypothetical cocktail partygoers asking him when he planned on getting serious. At this point, Richard Bachman didn’t technically exist yet. Rage wouldn’t be published for another year or two. Roadwork’s intentions consisted of showing the world that King could write more than horror, that he was a man of many talents. He also wrote it in response to his mother’s slow, painful death from cancer the previous year. King has stated he suspects Roadwork is the worst of the Bachman books because “it tries so hard to be good and to find some answers to the conundrum of human pain.” It has probably also sold the least of any of his novels.

THE RUNNING MAN

Most people see the above title and think of the 1987 film adaptation starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Like The Shawshank Redemption, not everybody initially believes this is based on a work by Stephen King—or Richard Bachman, for that matter. Although the novel is very different from the film, the same basic story remains in place. A gameshow called The Running Man exists in a dystopian society. The show’s contestants are chased by mercenaries employed to kill them.

The writing here is frantic and insane. It is perhaps most famous for having been written in a period of seventy-two hours, and serves as the best example of the differences between Stephen King and Richard Bachman. Bachman’s writing is significantly darker than the majority of King’s titles, and that’s truly saying something considering who we’re talking about here. In a Stephen King novel, yes, bad things happen, but usually the good guy wins in the end. Evil rarely prevails. But in a Richard Bachman novel, all the rules go straight out the fucking window.

From “The Importance of Bachman”:

“Ben Richards, the scrawny, pre-tubercular protagonist of The Running Man, crashes his hijacked plane into the Games Authority skyscraper, killing himself but taking hundreds (maybe thousands) of FreeVee executives with him; this is the Richard Bachman version of a happy ending.”

THINNER

The previous four novels were written before King brought Bachman into this world. Until Thinner, he’d never started a first draft with the name “Richard Bachman” typed below the title. The idea for Thinner came to him during a low point in his life when he weighed well over two hundred pounds. His doctor ordered him to lose weight and cut out the smoking or face severe health consequences—such as a heart attack. King left the office pissed off, upset with the fact that it wasn’t his choice to lose the weight but someone else’s. This downward spiral led to Bachman’s fifth novel.

King was so confident about this new book, he suggested to the publisher that they release it in hardback instead of paperback. They even came up with a phony author photo to slap on the dust jacket, which actually turned out to be the insurance agent of King’s literary agent. Thinner’s initial run sold a total of 28,000 copies. (After Bachman was outed, it unsurprisingly sold an additional 280,000.)

THE DEATH OF BACHMAN

King became convinced he could push Bachman onto the bestsellers list and started working on a novel titled Misery. This is the one, he thought. Misery would be Bachman’s much-deserved breakout success. And, if you think about it, Misery is totally a Bachman novel. The writing styles of King and Bachman each possess their own quirks, and Misery has Dicky written all over it.

However, it was during the writing of Misery that everything fell apart. King received a letter from a bookstore clerk named Steve Brown claiming to have discovered quite the bombshell while snooping around the Library of Congress: Stephen King’s own name was still listed as the copyright holder for Bachman’s debut novel, Rage. King could longer continue denying the truth. The jig was up. He agreed to an exclusive interview with the bookstore clerk, and the interview was eventually published in The Washington Post. While many had suspected Bachman’s true identity for years, they finally knew with certainty:

Richard Bachman was Stephen King.

But they didn’t seem to realize that Stephen King was also Richard Bachman.

So King did what he did best: He killed him. Claimed he died from “cancer of the pseudonym, a rare form of schizonomia.”

But that wasn’t enough. Bachman deserved a better death than some half-assed joke. If King was going to really kill him, he was going to do it with style.

Thus: The Dark Half. Published in 1989, not under Bachman’s name, but King’s. A novel about a writer killing off his pseudonym and the pseudonym resurrecting as a physical presence. It is by far one of the coolest of King’s works, and a fitting end to the legacy of Bachman.

Or, at least, until 1996.

THE REGULATORS

While working on a new novel, Desperation, King kept returning to a single word: “REGULATORS.” He wrote it down on a piece of scratch paper and taped it to his printer. The early signs of a new novel began seeping through: something about toys, guns, and suburbia. Then, one rainy day while backing out of his driveway, King was hit with an epiphany. He suddenly knew exactly what to do.

“The idea was to take characters from Desperation and put them into The Regulators. In some cases, I thought, they could play the same people; in others, they would change; in neither would they do the same things or react in the same ways, because the different stories would dictate different courses of action. It would be, I thought, like the members of a repertory company acting in two different ways.”

He also realized it would be even more exciting to write The Regulators under Bachman’s name and Desperation under his own. Sure, Bachman was dead, but when did that ever stop anybody? King claimed Bachman’s widow discovered this new book from the mythical “trunk” and released both Desperation and The Regulators simultaneously, both jacket covers connecting to form one large image. New novels by two different authors, mirroring each other.

BLAZE

After Carrie was published in 1974, King offered Doubleday two new manuscripts: a vampire novel titled Second Coming and another one reminiscent of the Lindbergh kidnapping. His publishers eventually decided to go with Second Coming, which would go on to be called Jerusalem’s Lot, which would then be shortened to Salem’s Lot. Afterward, King stated in various interviews how relieved he felt since, looking back, he realized just how fucking terrible the other novel actually was. He vowed it would never see the light of day. So, of course, it makes sense that in 2007 he broke that vow and released it anyway. To be fair, he claimed to have heavily rewritten the manuscript beforehand.

FUTURE WORKS

Since the release of Blaze, no other manuscripts have turned up in King’s attic, and sometimes I fear we’ve seen the last of Dicky. Anyone familiar with Stephen King’s massive bibliography is probably aware of his many unfinished or unpublished manuscripts. Obviously there are reasons they were never released to the public, but one can hope someday a couple of them might peak King’s interest again. Perhaps some might fall under Bachman territory. I can’t help but think about an unfinished book attempted around the time of Carrie’s publication, titled The House on Value Street.

From Danse Macabre:

“It was going to be a roman a clef about the kidnapping of Patty Hearst, her brainwashing, her participation in the bank robbery, the shootout at the SLA hideout in Los Angeles, the fugitive run across the country, the whole ball of wax.”

Tell me that doesn’t sound like a goddamn Richard Bachman novel. Unfortunately, King had trouble finding the right angle into the narrative, and before he could figure it out he became obsessed with a different project: The Stand.

I still have hope that one day he’ll return to it. I need The House on Value Street in my life, and so do you, even if you don’t realize it yet.

A BACHMAN STATE OF MIND

According to King, a Bachman state of mind consists of “low rage and simmering despair.” You can almost feel King punching his typewriter in Bachman’s prose. These novels come from an angry and frustrated place—two of the necessary ingredients required for creating raw, emotional fiction. When you open up a Richard Bachman novel, you aren’t just reading something Stephen King wrote and slapped someone else’s name on. Bachman is not simply another pseudonym. He’s something much darker.

For further conversation about King's pseudonymous history, I recommend tuning into my Richard Bachman episode of Castle Rock Radio (A Stephen King Podcast).

Get The Bachman Books at Amazon

To leave a commentLogin with Facebook