How Is Magical Realism Different From Fantasy?

If you're a book reader and a fan of literature in general, you've probably already heard the term magical realism. You might also know that the term originally applied to a particular brand of fiction coming out of Latin America in the 20th century—primarily from writers Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez, Laura Esquivel, Isabel Allende, and numerous others—but has now become a subgenre all its own, with authors around the world contributing works that fit the mold. A magical realism text, in short, involves elements of magic, the supernatural, and even the surreal entwined with everyday, even mundane activity.

If you've never heard this term before, you might be thinking to yourself, isn't that just fantasy? Or some other type of speculative fiction—horror, even?

And that's a valid question. What separates magical realism from the pack?

Emma Allman offers this distinction in her essay on the subgenre for Book Riot:

...magical realism uses magical elements to make a point about reality. This is as opposed to stories that are solidly in the fantasy or sci-fi genres which are often separate from our own reality. There is a distortion effect in the very fiber of the prose that forces the reader to question what is real and often opens up avenues of reality we may not have thought possible before reading the story. The realities being questioned can be societal, familial, mental, and emotional, just to name a few.

Another tenet of magical realism is the way in which the characters respond to the unrealistic events occurring around them, usually without much fanfare, as though magic were just as commonplace as a kitchen sink. Take for instance Gabriel García Márquez's seminal work One Hundred Years Of Solitude, a sprawling novel covering a century in the life of the Buendía family. Reportedly inspired by folklore tales told to a young García Márquez by his grandparents—tales that were presented as fact, causing the boy to confuse reality and fantasy, i.e., to believe in a world where magic actually exists.

The author brings this lack of distinction between fantasy and reality into the novel, which is set in a fictional Columbia town, Macondo. And yet, the very fact García Márquez's narrative takes place in a made-up locale, calls into question the idea One Hundred Years Of Solitude is an overall realistic novel peppered with elements of the fantastic. Recall Allman's definition of magical realism above, which asserts the subgenre is "opposed to stories that are solidly in the fantasy or sci-fi genres which are often separate from our own reality." While Solitude references actual locations, one can argue that it is not, in fact, set in the real world, given its primary setting is invented, and given that it presents a world in which magic is not only real, but taken for granted.

The author brings this lack of distinction between fantasy and reality into the novel, which is set in a fictional Columbia town, Macondo. And yet, the very fact García Márquez's narrative takes place in a made-up locale, calls into question the idea One Hundred Years Of Solitude is an overall realistic novel peppered with elements of the fantastic. Recall Allman's definition of magical realism above, which asserts the subgenre is "opposed to stories that are solidly in the fantasy or sci-fi genres which are often separate from our own reality." While Solitude references actual locations, one can argue that it is not, in fact, set in the real world, given its primary setting is invented, and given that it presents a world in which magic is not only real, but taken for granted.

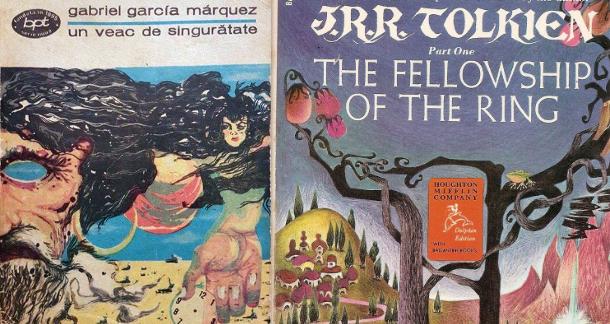

In this sense, how is the fictional world of Macondo any different from, say, Middle-earth? Yes, there aren't elves and hobbits and wizards in Solitude, but the very founding of Macondo is a fantastical event not unlike the creation myths of various religions, seeming to metaphysically spring forth from the mind of José Arcadio Buendía; there are also ghosts, clairvoyants, and, as The Guardian writer Sam Jordison names them, "floating virgins, reincarnating gypsies and soothsaying colonels." All the events and ostensibly unreal circumstances are a result of meticulous world-building on the part of García Márquez, and while not as "out-there" as anything written by J.R.R. Tolkien, are the two approaches to storytelling really so different?

This same argument can also apply to one of magical realism's other tenets: the presence of sociological and political commentary. Indeed, Solitude examines, according to Encylopedia.com, "the political, social, and economic turmoil of a hundred years of Latin American history"—much like numerous other titles in the Latin American magical realism tradition, which Allman calls a "a genre of political subversion"—but you can find sociopolitical commentary in the likes of A Wrinkle In Time, the Harry Potter series, and even (supposedly) The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz, to say nothing of the political dystopian novels 1984, Farenheit 451, and The Handmaid's Tale, to name only a few. In fact, it isn't a stretch to say 99% of literature has some kind of underlying message concerning politics and/or society, and so commentary of this kind doesn't necessarily distinguish magical realism from other genres.

However, all the fantasy novels mentioned above have one thing in common that you won't typically find in magical realism texts: the presence of a protagonist who acts as a stand-in for the reader, an uninitiated individual, an outsider, who enters into fantastic realms and learns how they operate from those in the know. This is even the case in Tolkien's work: both Bilbo and Frodo—fantasy beings in their own right—go on amazing journeys, in which they encounter thrilling magic, both in a negative and positive sense, that they have never seen before. By contrast, hardly anyone in a magical realism story reacts with surprise to the unreal or supernatural occurrences surrounding them. These fantastic things simply happen, are simply a part of the world they occupy.

However, all the fantasy novels mentioned above have one thing in common that you won't typically find in magical realism texts: the presence of a protagonist who acts as a stand-in for the reader, an uninitiated individual, an outsider, who enters into fantastic realms and learns how they operate from those in the know. This is even the case in Tolkien's work: both Bilbo and Frodo—fantasy beings in their own right—go on amazing journeys, in which they encounter thrilling magic, both in a negative and positive sense, that they have never seen before. By contrast, hardly anyone in a magical realism story reacts with surprise to the unreal or supernatural occurrences surrounding them. These fantastic things simply happen, are simply a part of the world they occupy.

This nonplussed reaction to the strange and unusual may be the best qualifier for magical realism as opposed to other speculative works. But even then, should you find yourself reading a story in which the characters don't react with the level of surprise, or even shock, toward the unbelievable things happening around them, you're not necessarily reading a magical realism text, at least not strictly. This brings us to considerations of horror in our discussion, especially texts that interject aspects of magical realism into the mix. Author Helen Marshall outlined a few such stories in a guest blog post for My Bookish Ways in 2012, from writers who defy typical conventions of horror by presenting "the 'strange'—their rupture from reality—upfront: they normalize it. They don’t explain it. It simply…is." Marshall specifically cites Robert Shearman and Karin Tidbeck as crafters of this magical realism-horror hybrid, and alongside them, consider Pasi Ilmari Jääskeläinen's The Rabbit Back Literature Society, Ali Shaw's The Girl With Glass Feet, and Gwendolyn Kiste's The Rust Maidens.

But does any of this genre-labeling matter? In a sense, yes, if you're looking for a specific kind of book to read—i.e., you're interested in horror narratives featuring characters that lean into, rather than react against, the strange, or you're interested in that distinctly magical realistic indifference to the strange without elements of horror. Overall, though, magical realism is really just a way of describing fiction that refuses to stick within the confines of the world we see before us, as well as remind us that the actual world can be just as strange and surreal as fictional landscapes.

0060883286

1947654446

To leave a commentLogin with Facebook